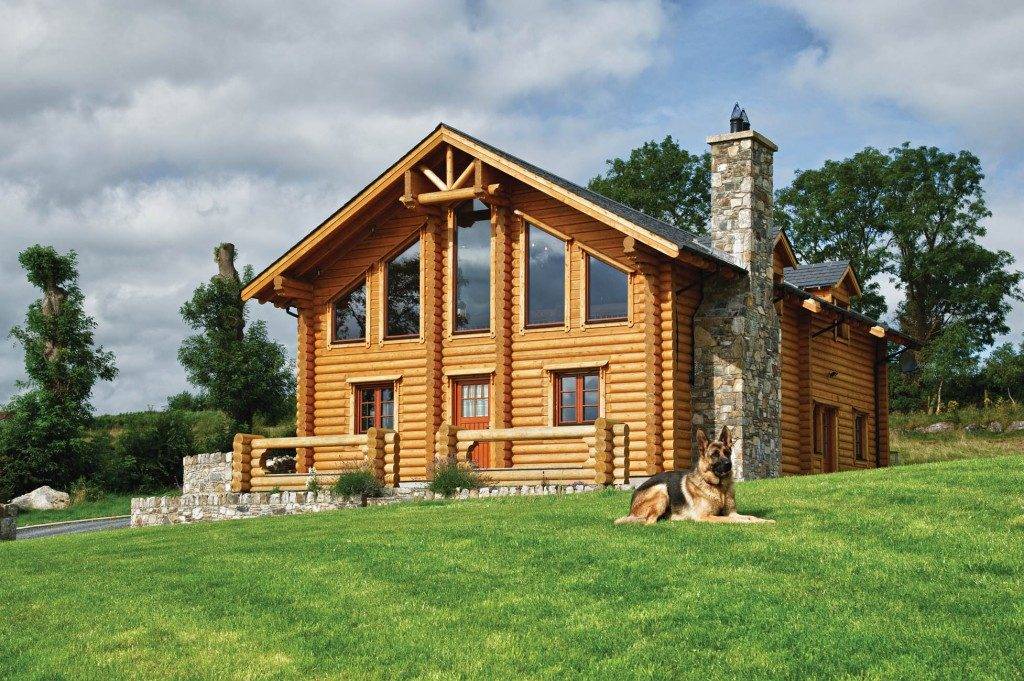

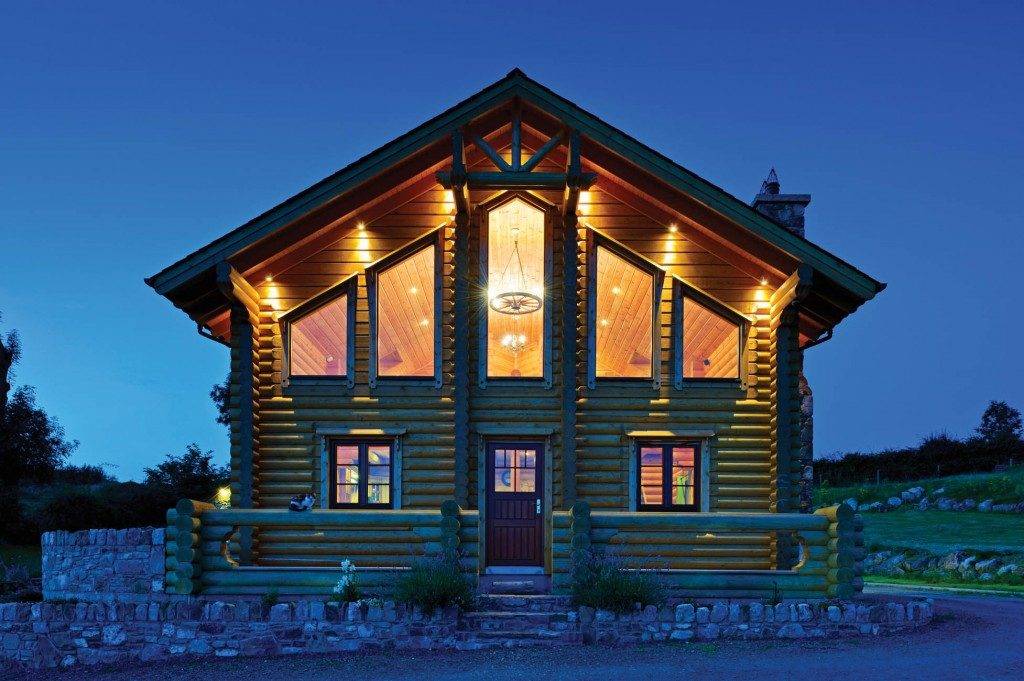

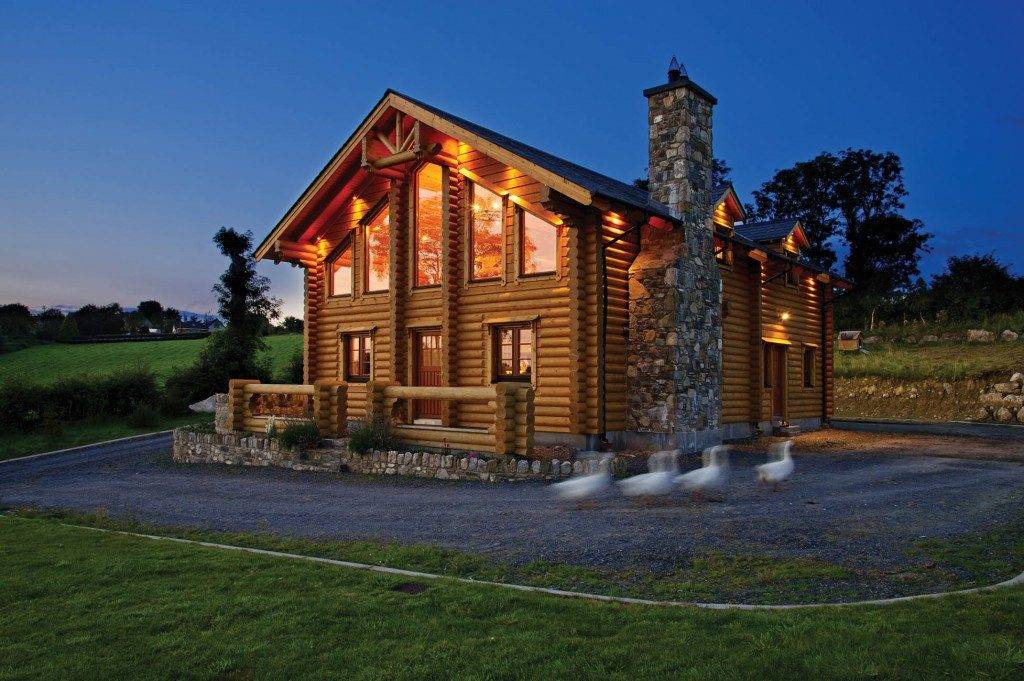

Lee Conlon’s determination to build himself a log house in Co Monaghan shows just what can be done when you know exactly what you want.

In this article we cover:

- Financing the build and final build cost

- Deciding on the build method, benefits of log homes

- Planning permission

- Direct labour tips, finding the trades, how to stay on schedule

- Timeframe and all steps involved, from the foundations

- Assembling the logs when they arrived on site

- What type of timber he chose and why it paid off to pay double

- Window installation

- Staircase and internal walls

- Stone fireplace details

- Professional photographs

- Specification and supplier list

Overview

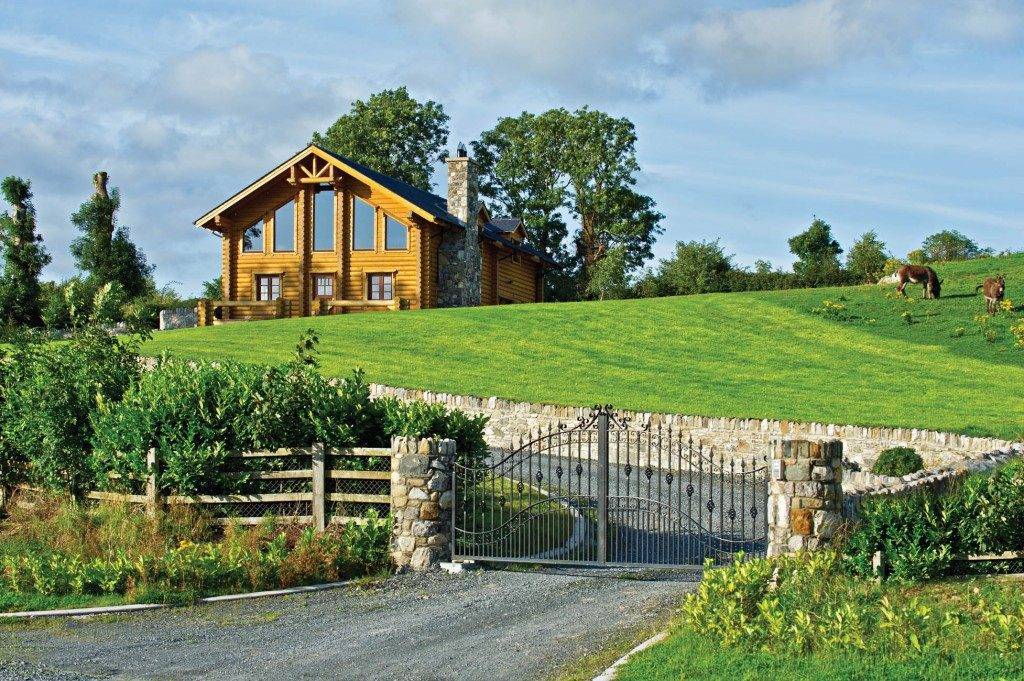

Site size: 4 acres

House size: 2,100 sqft

Total cost including kit, fit-out and furnishings: €296,000

More often than not, building your own house comes with a specific set of challenges, including securing planning permission as well as getting a mortgage. In Lee’s case, the difficulties started with the plot, and came from the tax man. “I inherited the site from a friend when I was 14, and the deeds were passed on to me when I turned 20, I’m now 25,” he says. “The transfer in ownership meant I had to get a mortgage to pay capital gains tax.” For all intents and purposes, this was the equivalent of buying the site outright.

“There was an existing house on the land but it would have cost a considerable amount to do it up,” he says. “I would have been confined to having to work within the four walls and I couldn’t see how the layout could be reconfigured to suit my needs, so I decided to build a new house.”

“When I started it was the height of the property boom, but thanks to planning delays I broke ground in 2010, so prices had come down by then,” he says. “But at that stage I was very unlikely to get a mortgage. I’d given up all hope when a local broker got it for me.”

Eco motto

Interested in environmentally friendly houses, Lee went around visiting 15 to 20 homes throughout Ireland to get a feel for the different types available, and he quickly realised what he wanted. “What drove me towards building a log house was how ecological they are; there’s hardly any man-made products used. I was determined to make the house eco-friendly and get as many locally sourced materials as possible. I had the ambition of achieving as low a carbon footprint as I could, which is surprisingly hard to do in Ireland.”

“I did a lot of research on the topic and like most people, I had to consider the fire hazards of building a log home. But if you think about it, if you light a match to a log, it won’t burn, it’ll just char…it’s too dense. Tests carried out in the US proved that log homes actually last three times longer than conventional timber frame,” he says. “In my line of work as a fireman I’ve been to quite a few house fires and the type of construction doesn’t always affect how long the house will stay standing. With wood, the charcoal generated in the combustion process forms a natural insulating layer during a fire.”

The timber regulates the indoor climate, reducing and keeping the humidity levels constant. “The benefits are many,” he adds. “The logs allow air through, so the house breathes, but in such a way that the air is filtered. There’s a lot less dust in log homes, apparently they are great for asthmatics. There’s also a fresh pine scent coming from the essential oils in the wood, which people usually comment on when they step into the house, but I don’t even notice it anymore.” The timber regulates the indoor climate, reducing and keeping the humidity levels constant.

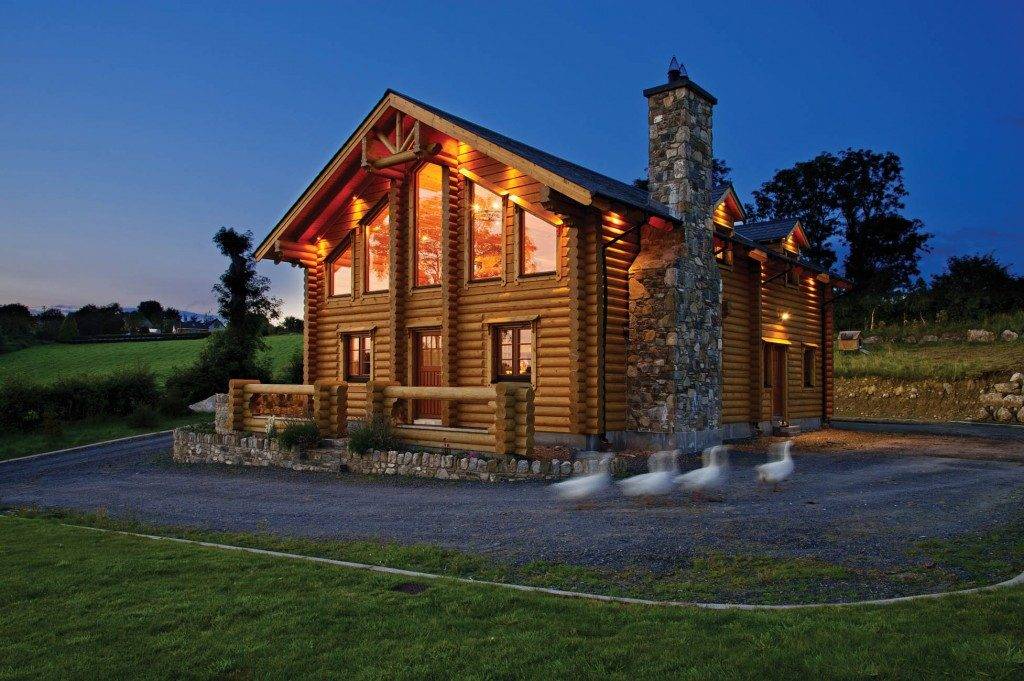

Lee planned the build very carefully and designed the house so that it would be facing south to make the most of the solar gains, but this led to a disagreement with the planners. “They wanted me to build the house along the natural boundary lines, but that conflicted with the south facing ethos of the project,” says Lee. “They also didn’t like the look of the log house, they said it didn’t fit in with the natural environment. I told them I was surrounded by trees, of course it fitted. I did make some concessions, for instance they didn’t want me to build a balcony out front so I didn’t.”

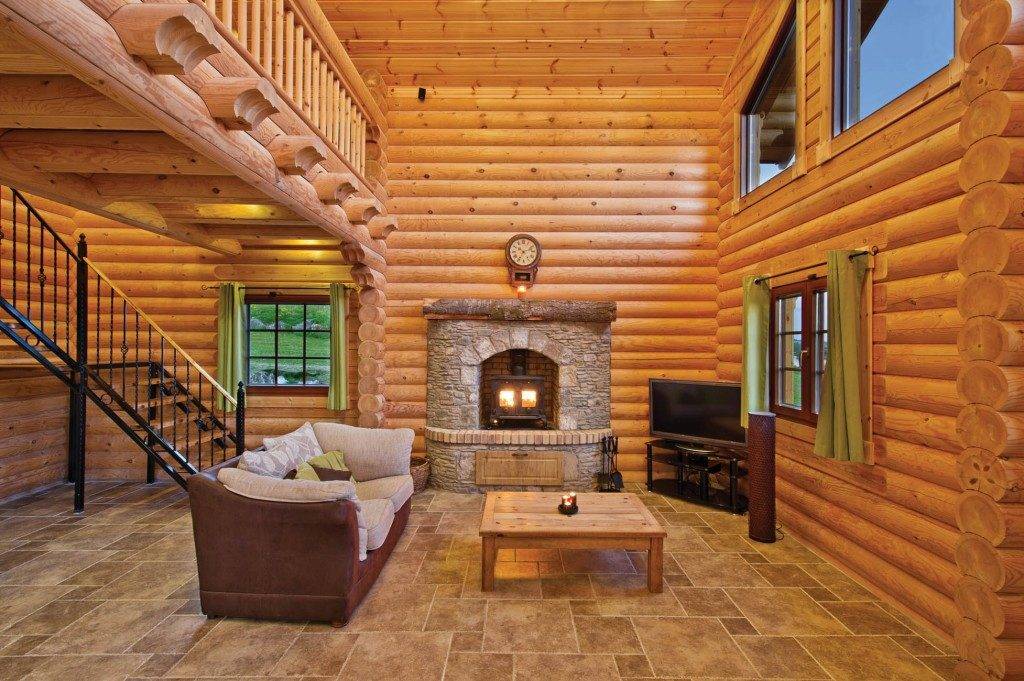

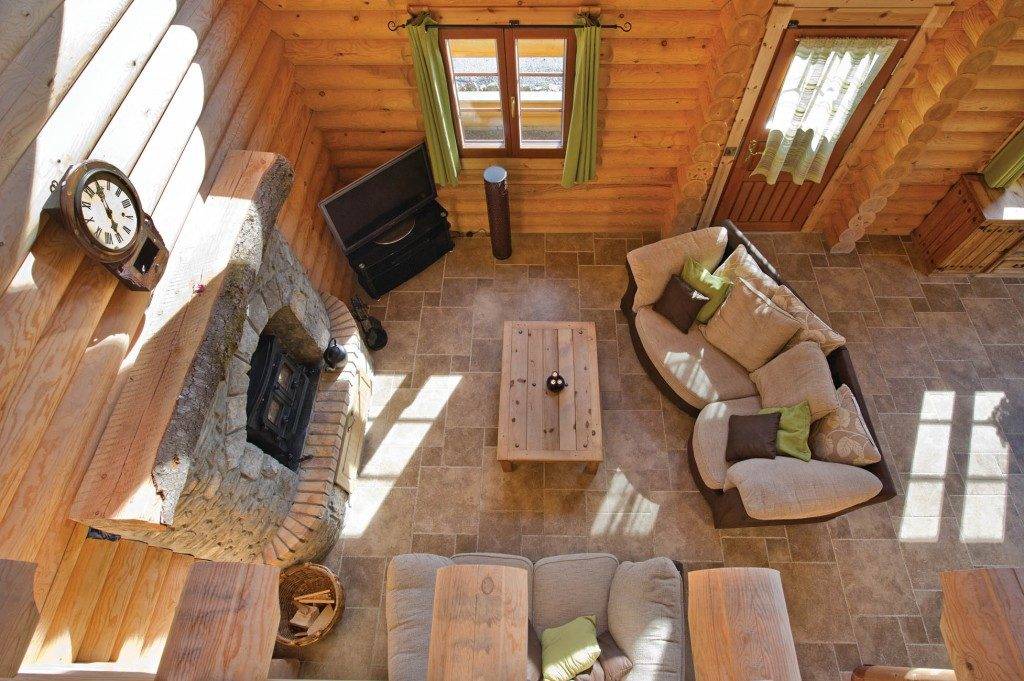

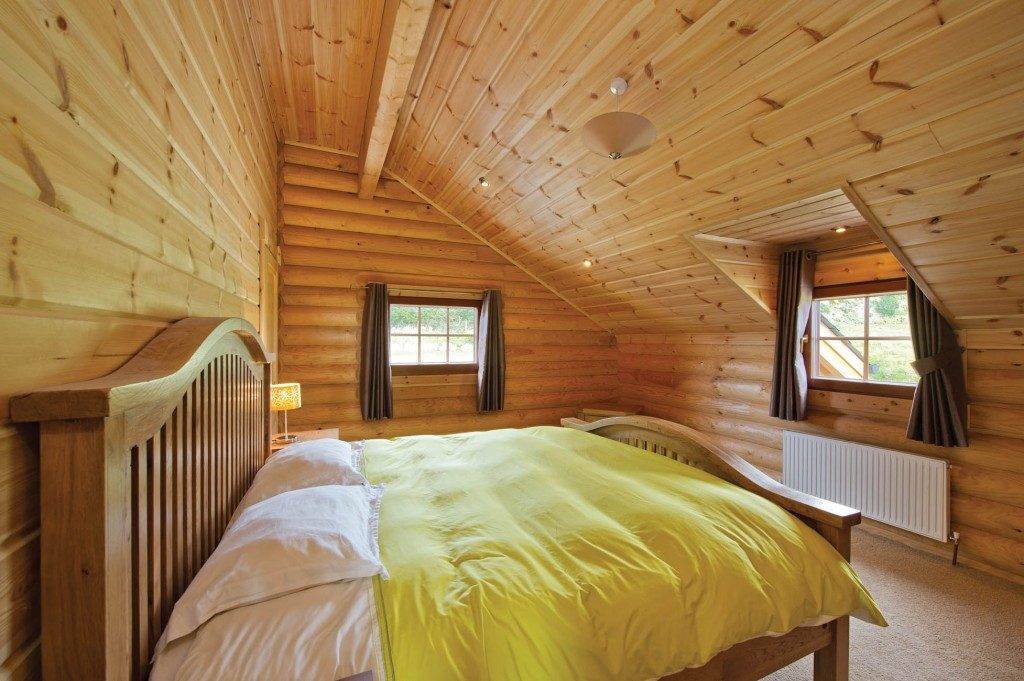

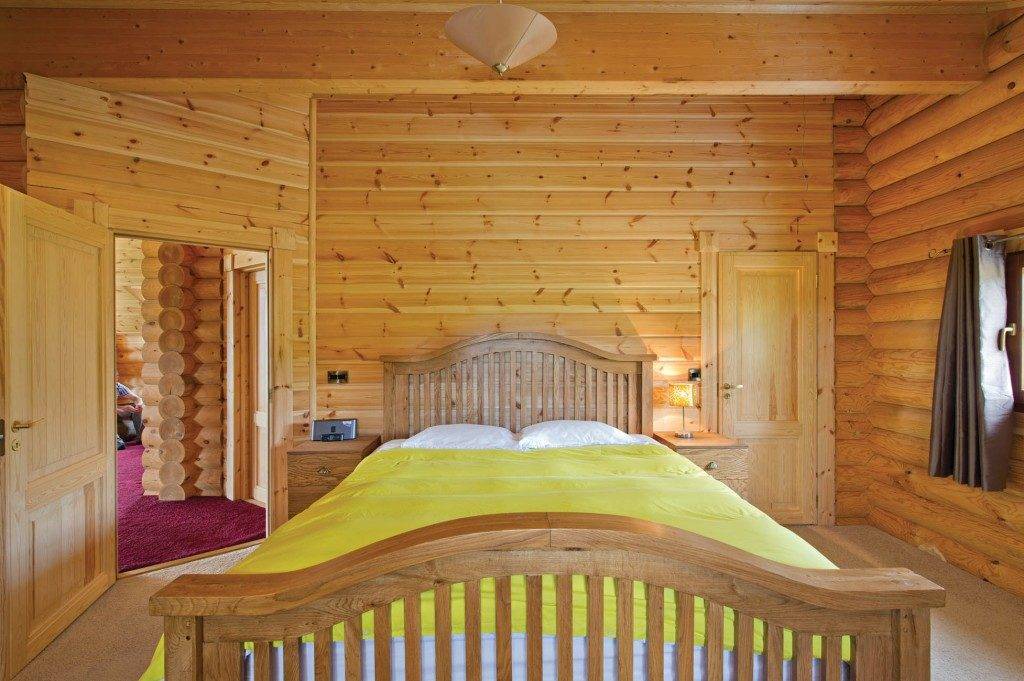

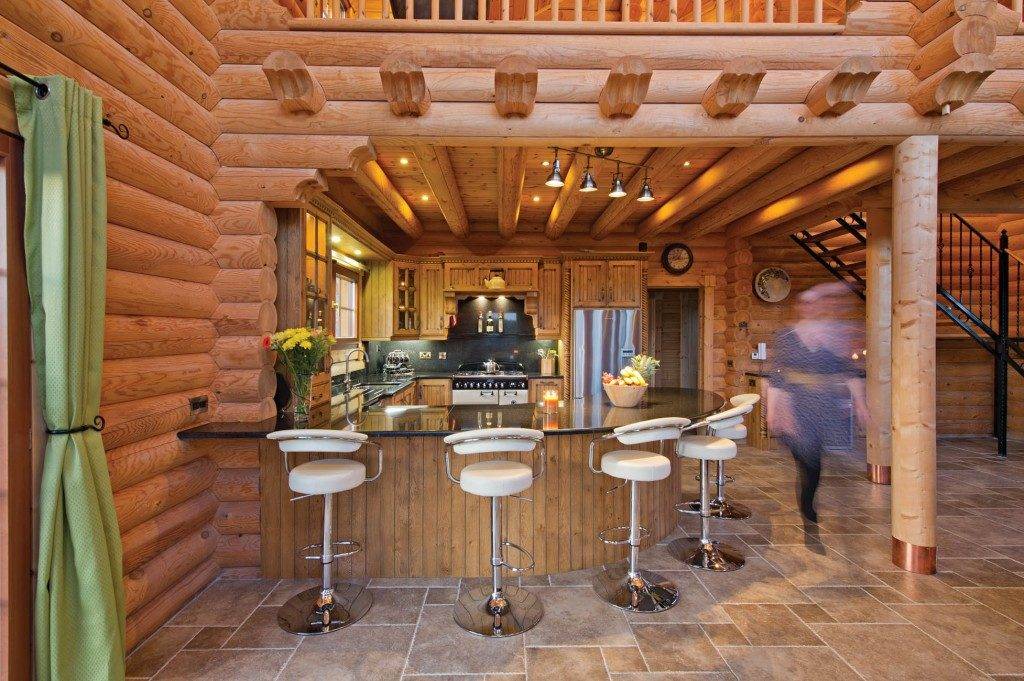

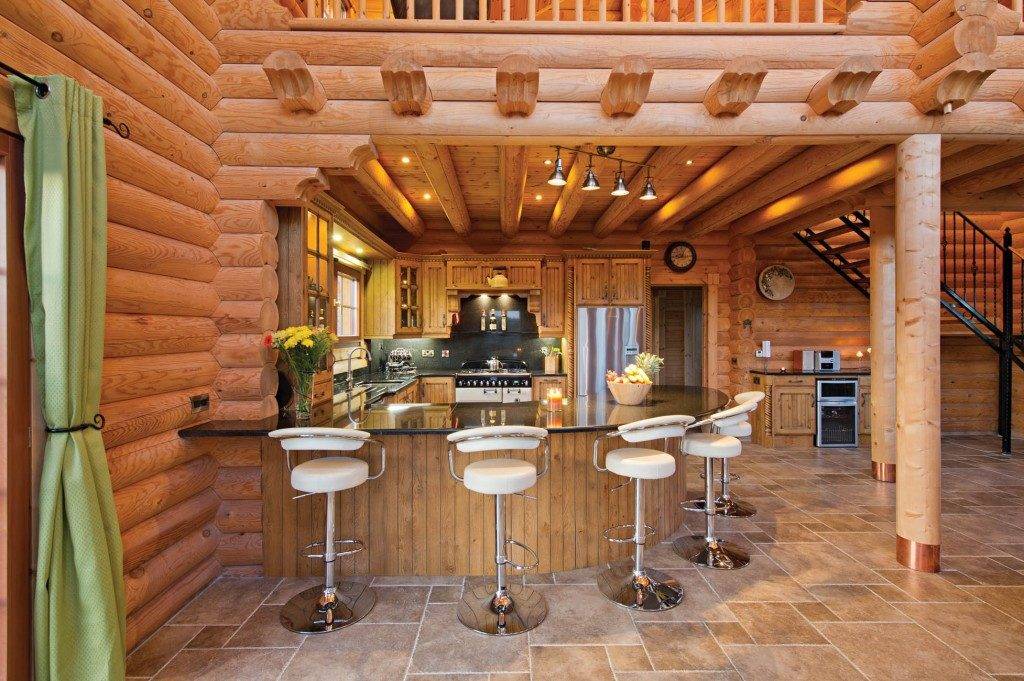

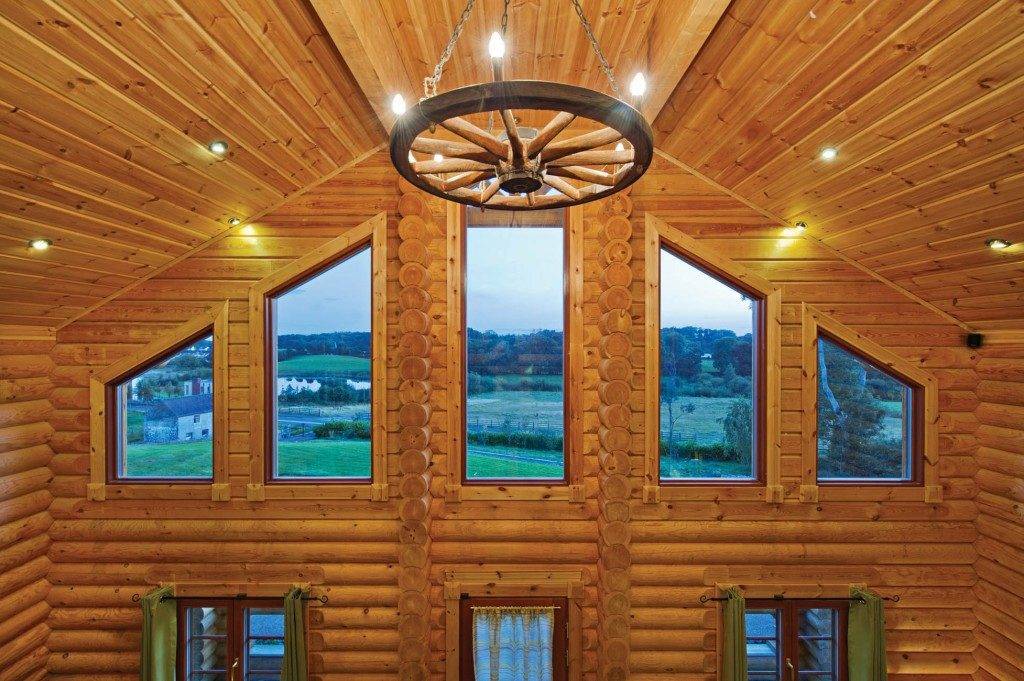

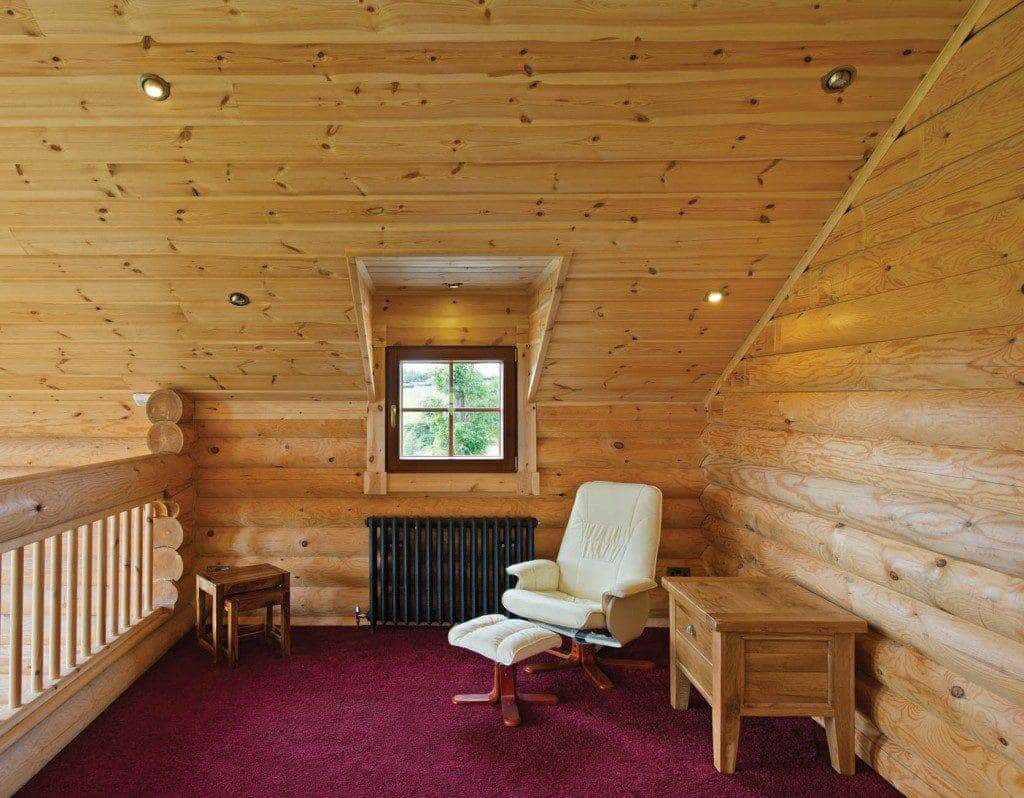

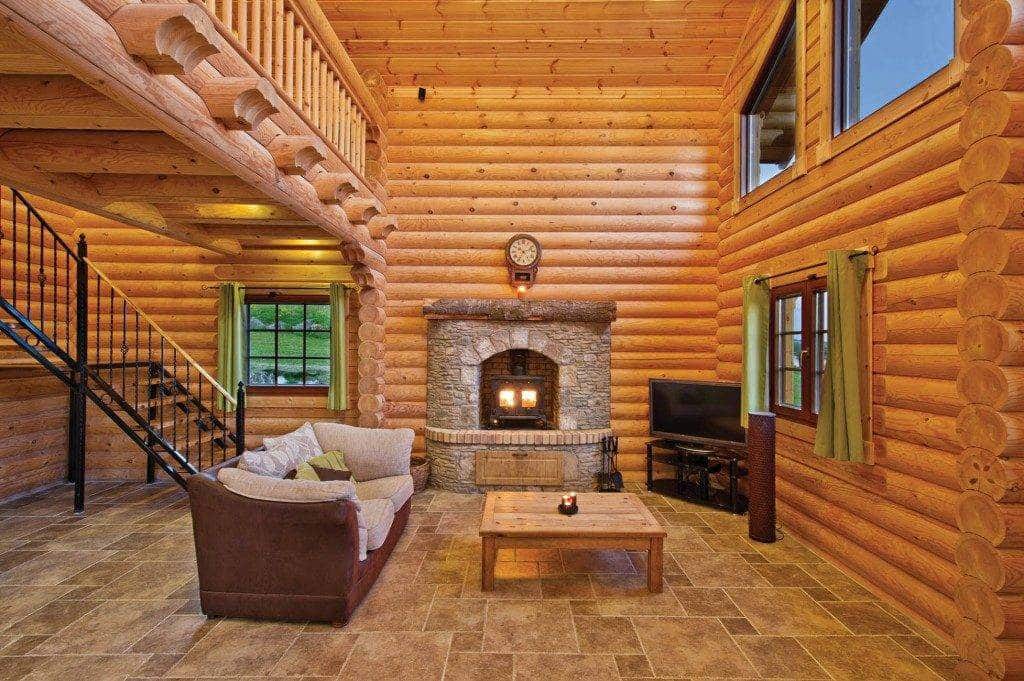

The planners rejected Lee’s plans twice. “I kept at them and I got consent on the third go,” he adds. “It took three years in total, including the design.” The plans, devised in association with the log supplier, were tailored to suit his lifestyle. “From my experience living at home with my parents, if people came to visit they always hung around in the kitchen – the good room was only ever used at Christmas.,” says Lee. “So I designed it for there to be an open plan living area with kitchen, full height to the roof, with an internal balcony over it. On the ground floor there’s also a bathroom, two bedrooms, (one currently used for storage), and upstairs there’s two additional bedrooms one of which is an en-suite.”

Lee is very happy with how the space is working out, and when he’s cooking something that has a strong smell, he turns on his ‘extra strong fan’. “As the house was designed to be airtight, I had difficulties in finding a way of making the vent from the kitchen fan not attract wind gusts when not in use. In my work as a contractor I came across a four inch non-return valve for sewer pipes, which I revamped to suit the duct pipe from the fan. This allows for air to travel only one way when the fan is on.”

Log house log-istics

Lee took a few months leave to manage the build, and despite putting himself under pressure he would recommend anyone building their home to do likewise. “There were big savings managing the project, although I admit it was very stressful organising all the trades,” he says. “I also did as much as I could myself, there really was a lot of work. Because the house was prefabricated there were predrilled holes for the electrical sockets, all of which were well insulated. I got a local plumber in, and helped him with the pipes which saved on labour costs but he did all the major works; same with the electrician.”

“I’d get a lot done at night, getting things ready for the trades and of course tidying up after them each evening. I also had to get everything priced, which took a while. I’m glad I managed it myself, now I know where everything is in the house, down to the last piece of wire.”

“Doing most of the work myself and seeing everything through meant it was done right. When working to a price, some contractors might skimp on things to get the job done more quickly. I have to say I wasn’t happy with everyone who worked on the build, the airtight membrane installers weren’t great, I had to tape up behind them, otherwise it would have been overlooked and covered up, I wouldn’t have known until an airtight test was carried out. It was important for me to be here and see everything that was going on.”

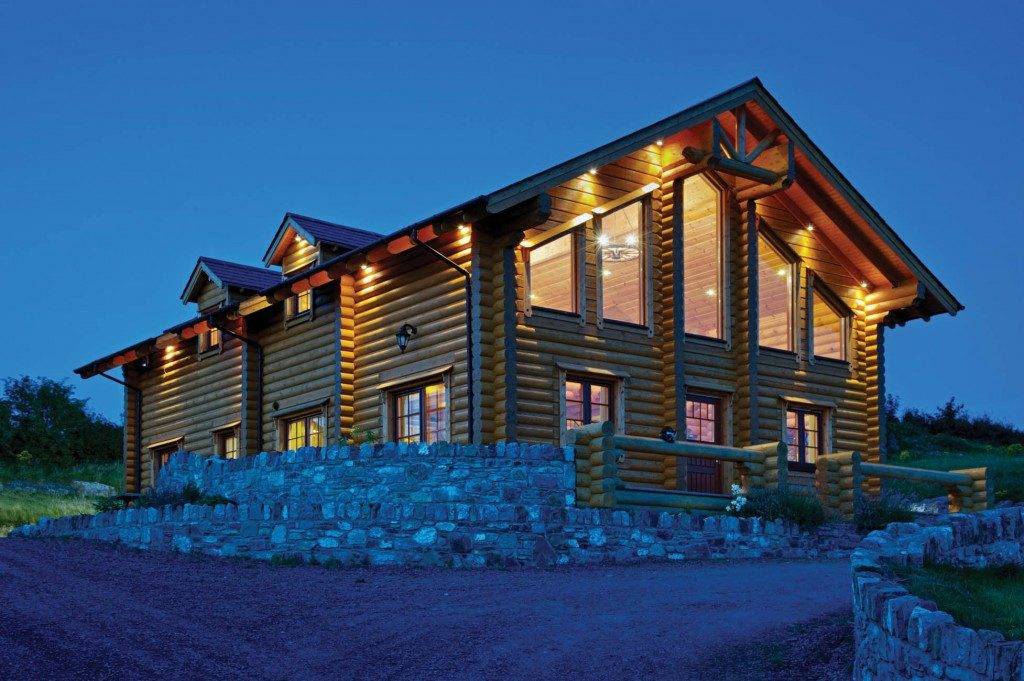

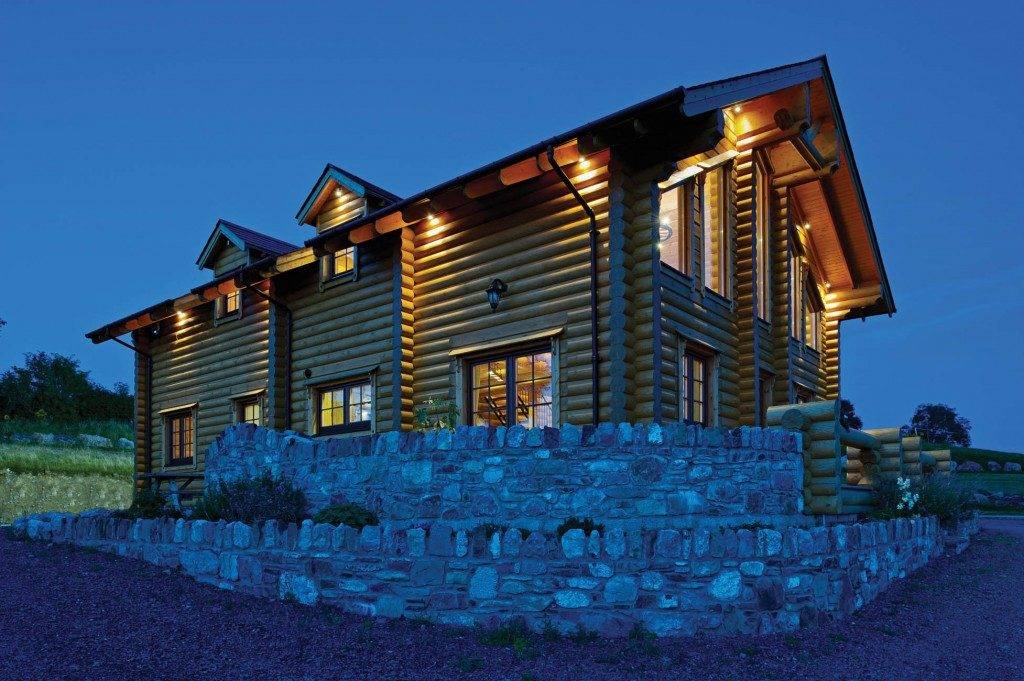

Lee arranged for the foundations to be put into place before the logs arrived on site, but first he had to create a 40m platform on which to build his home, as the design called for a level site. “I ended up excavating quite a bit because the site is sloping; we dug four metres into the hill,” he says.

“We kept the stones and boulders with which we built the retaining walls. It would have been just as handy to dump them, but I wanted the area around the house to be as natural as possible, and the carbon impact minimal. I could’ve gone for a block or mass concrete wall, and probably would have spent just as much, but it wouldn’t have looked the part. It took up to an hour to move a single boulder, but I think it provides such a nice visual effect, especially with small shrubs and flowers in between.”

“Once I knew the delivery date of the logs, I set out building the foundations,” he adds. “Myself and a local builder built to floor level. I then insulated the floor, installed the underfloor heating pipes and finally poured the floor.”

The logs arrived on three curtainsider lorries; each piece of wood labeled according to the position it was to take. “It was like a big 3D jigsaw,” says Lee. “There were 29 walls in total, each going up 30 something logs high. The log company’s Irish representative was there to help us put up the first couple of logs, he was very helpful throughout the build, from the design stage to the snagging phase.”

Lee and two carpenters put up the log frame within five weeks; he says that once they got the hang of it, they had a great time. “Once we got over the first couple of logs, it was easy enough,” he says. “Getting to four logs high was the hardest part because the higher you go the more weight there is, and therefore more stability.”

Once they got to eight logs high they had to bring in scaffolding, and they used a teleporter to put the logs into place. “Every half metre there’s a 28mm hole in the log and a 30mm dowel is then driven into the logs to hold them together,” says Lee. “The top of each log is lined with an insulation membrane prior to placing the next log on top of it. Four teeth on the underside of the log then dig into the membrane and log beneath, creating an air and water tight seal.”

“There’s a great feeling to building your own home,” he adds, “and with a log house, at the end of the day you can really see the progress made. I’m not a skilled carpenter, I’m a contractor and fireman by trade, so it was great to realise I’d actually built my own home”

Then came the roof, which Lee says was simple enough to build. “Along with the carpenters we put in seven inch rafters, the timber for the roof was manufactured in the log supplier’s factory but I had to source the slates myself. I’d built the garage before the house so all of the windows and other later additions were stored there.”

The walls of the house consist solely of the logs, which are 230mm thick. So without any insulation to speak of, it may be surprising to learn that the house is actually quite easy to heat. “The poor U-value doesn’t take into account that logs have excellent thermal mass,” says Lee. “It really works, it moderates the inside temperature really well. In the winter the underfloor heating is on at a constant low temperature throughout the house and the stove in the main room is able to heat up the whole house – if you leave the doors open it’ll heat the bedrooms.

When I was looking at heating systems I was originally going to go for a heat pump but at €20,000 it wasn’t going to deliver the value for money in a home that’s so easy to heat. So I chose a condensing oil boiler, and now spend about €800 a year in heating oil. I still have some timber left from building the house so that’s free fuel for the stove.” Flat plate solar panels supply most of his hot water, in the winter it’ll heat it up to at least 45°C.

The walls may not be insulated, but the same certainly can’t be said of the rest of the building elements. “I went a bit crazy on the insulation of the floor and roof,” admits Lee. “For the roof, considering the amount of recycled newspaper I put in, it probably was enough but at the time I thought I might as well insulate between the battens with sheep’s wool. It’s a really nice material to work with. I tried to use as many natural products as possible although I couldn’t find something other than polyurethane insulation to put underneath the concrete floor.”

Inside, just one of the walls is made of solid log. “It was too costly to do all of the internal walls in log so I went for 3/4 inch battened stud partitions, with a timber finish of natural pine. I strived to use as few man made materials as possible, so there’s no plaster or concrete. To soundproof the walls I insulated them with recycled newspaper.”

Settling into the log house

In the majority of the houses Lee visited he noticed the logs had cracks in them. “Most of the manufacturers have their logs brought in from North America or maybe Latvia or Estonia, where the wood is often grown quite quickly, and when it starts adjusting to its new climate and to the load, it can crack,” he says.

“The company I chose, despite being twice the price of the cheapest supplier, has its wood supplied from Finland, a country with a very good woodland policy. For every tree that’s felled two are planted in its place. And despite the wood being pine, a softwood, it acts much like a hardwood because it’s taken 80 to 100 years to grow under Arctic conditions, which means the rings in the logs are tighter and more dense than regular pine; it’s called arctic pine.” The company he chose was also the only one at the time to be able to provide the CE mark.

“The difference in quality was palpable in the houses I visited,” adds Lee. “The Finnish pine was in a different league.” The manufacturers have a patented method which involves splitting the logs in two to dry out the timber and reduce the moisture content to 15 per cent, which also helps minimise cracking. The logs are then laminated back together.

“Unless you look very closely you can’t see where they’ve been laminated,” says Lee. “Splitting the wood purposefully means that if a crack does form, it will never go straight through the beam.”

“My house settled 2.5 inches over two years and while that’s most of the settling done, it’ll continue to move slowly for the rest of its life.”

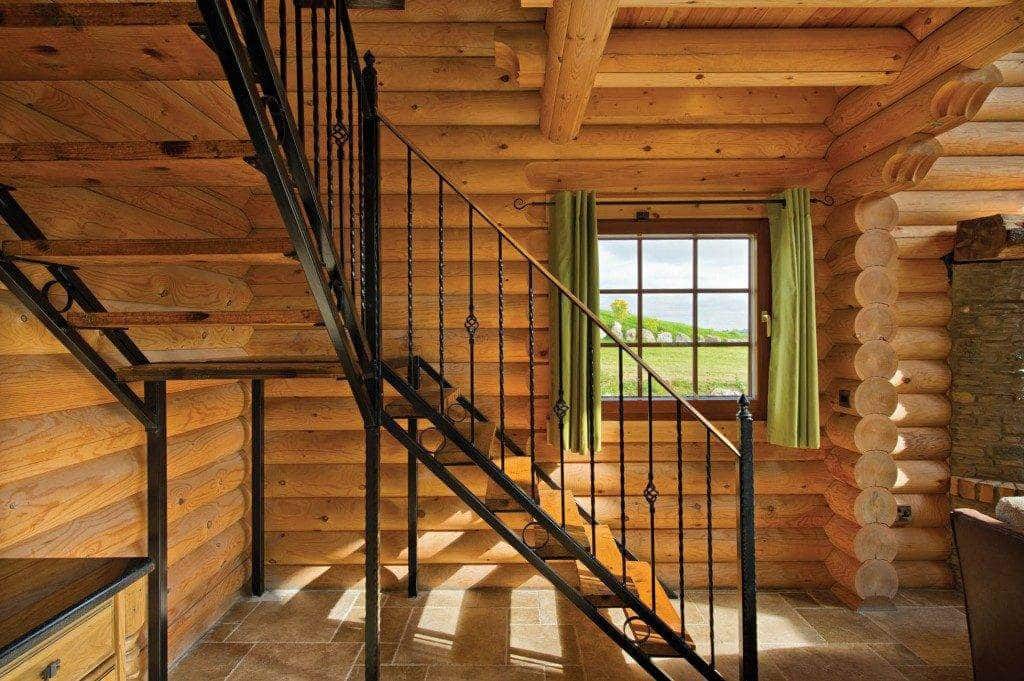

In fact all logs homes tend to show signs of settling – as a living structure, the house shifts and does most of it over a period of two years. “The issue of settlement I picked up from other people who hadn’t realised the extent to which their house would move, so they warned me about it. My house settled 2.5 inches over two years and while that’s most of the settling done, it’ll continue to move slowly for the rest of its life.” Attaching anything to the logs early on could damage it or the wood itself, which clearly had repercussions on how to install things like windows and doors.

“When we installed the windows we allowed for a four inch settlement gap between the logs and the window frame and covered the whole lot with hemp in roll form, an airtight membrane and the architrave. The architrave is essentially attached to the window, not to the logs.”

The staircase presented a similar conundrum. “For the stairs I got a local man who makes gates to use cast iron. Because everything else in the house is timber I thought it would work well to change material, to provide contrast,” says Lee. “Log stairs would also have cost eight to ten thousand euros while the steel staircase came in at only €1,500. Because of the settlement issue we had to make sure it wouldn’t buckle in the first year of the floor settling, so we devised a mechanism that allows the staircase to slide on bolts. I used the same system with the kitchen units.”

In the bathrooms Lee considered tiling the walls but he thought the same issue of settlement could lead to problems. “I looked at fully enclosed shower units but I didn’t like them, instead I went for a glass block shower unit,” he says. “You can see the logs behind it, which is a nice feature. It was a bit dearer but worth it.”

As for the dormers, two forces were at play, the roof pressing out and the log walls pressing down. “It represented a lot of extra work putting them in, it took us a considerable amount of time figuring out how to deal with the timber and the lead flashing,” says Lee. “If we’d gone two logs higher we wouldn’t have needed the dormers but the planners wouldn’t allow for a higher ridge height, and I wanted to keep the roof pitch at the same gradient so there wasn’t much choice really.”

The stone fireplace was another nut to crack, the solution there was to build it free standing. “The chimney is actually 70mm away from the house. We added a settlement gap above the fireplace – where the roof meets the chimney stack is a tricky area, and so we used lead flashings that slide into each other to allow for the house to move. If I was doing it again I would’ve just put a flue in but I’m glad to have it, it’s a nice feature. Still, the whole thing set the budget back €10,000.”

Lee saved on other features, such as the old cartwheel chandelier in the living room. “I got it from a donkey’s cart, sandblasted it and got it wired up; it cost me €50.” The lights are all LED but Lee says he never turns them on during the day due to the five big south facing windows providing ample illumination.

In fact if there’s just one thing he would perhaps do differently it would be to add a sunroom. “It’s perfect for now, for my life as a bachelor but I can see how the space is almost too open,” he says. “If I ever have kids down the line it would be useful to have an extra room, and it would be a good place for people to go and have a private chat. I could have made the house bigger for very little extra but I purposefully built it to the size I needed. A couple I know have five bedrooms, each with ensuites and they never use them. It’s just the two of them. Why build a house if you’re only going to live in a third of it – what’s the point?”

Indeed, what more can you ask for but a tailor-made home that’s eco-friendly and a delight to live in?

Spec

Construction: 230mm thick patented engineered logs, warm roof with natural slates

Insulation: exposed logs on walls, on floor 3x75mm rigid polyurethane boards, on roof 175mm recycled newspaper pumped between rafters and 50mm sheep’s wool between battens supporting 75mm timber panel

U-values: log walls 0.54 W/m2K, floor 0.18 W/m2K

Windows: argon filled, double glazed, U-value 1.1 W/m2K

Log house suppliers

Log house kit (including windows and doors): Honka Log Homes, www.honka.ie (kit manufacturer) Good Wood Solutions Ireland, Limerick, tel. 061 748 489, www.goodwoodsolutions.com (custom design services, management of kit production and delivery, unloading and site set up supervision, training materials and on-site consultancy during the start of construction)

Mortgage broker: Kelleher Insurance, Dundalk, Co Louth, tel. 042 939 1832, kelleherinsurances.ie

Staircase: Silverforge, Carrickmacross, Co Monaghan, mobile 086 312 1814, silverforge.ie

Electrician: CB Electrical, Carrickmacross, Co Monaghan, mobile 086 898 6938

Photography: Gareth Byrne, Dublin, tel. 01 406 2345, mobile 087 245 8089, garethbyrne.com, supplied courtesy of Honka Log Homes