Self-builder Paul Lawford explains why building a tiny house could be part of the solution to the housing crisis in Ireland.

In this article we cover:

- What is a tiny house

- How tiny is tiny

- How Paul built his tiny house

- The case for building a tiny house

- Setbacks and how he dealt with them

- Where he sourced materials

- What he’d do differently

- Pros and cons of tiny living

- How much energy he’s using

- Supplier list

- Other services

In 2019 I was ready to buy a house in Dublin. Unfortunately for me, Dublin didn’t seem as willing as I was. Short supply of adequate housing did not motivate me to invest €200k+ on a lemon. Not even a little.

Nearly four years later and, sadly but all too unsurprisingly, the situation nationally hasn’t changed a whole lot. For me however, it has.

Path to tiny house

The national housing emergency in tandem with the global climate crisis forced me to change the way I looked at housing. What really makes a house a home? Its scale? A concrete foundation? A mortgage? None of these things constitute a home. A home is a place you can live and grow in, contentedly and comfortably.

When I looked deeper at my options I wasn’t impressed. There’s the environmental impact of construction, a mortgage is hard to get and even if you do, you’re straddled with debt for years. A shocking number of my peers were also stumped by this, and I thought there must be a better way, there must be another option.

For me, that option presented itself in the form of the humble tiny house.

How tiny is tiny?

Tiny house is a loose term for – you guessed it – really small homes. There is no set definition of how small tiny is but think in the region of around 100sqft to 450sqft or roughly 10sqm to 40sqm.

The average apartment and house size in Ireland are 78.58sqm and 154.6sqm respectively. Averaging occupancy at 2.77 people for both, that’s 28.37sqm per person in an apartment and 55.81sqm per person in a house.

Per occupant, a tiny house averaging 12sqm is then 40 per cent smaller than the average apartment and almost 70 per cent smaller than the average house. Tiny houses, by their very nature, are far more environmentally friendly, quicker and cost effective to build than conventional housing. And what that really looks like is:

- 40 to 70 per cent less invested energy in materials

- 40 to 70 per cent less material costs

- 40 to 70 per cent less labour costs

- 40 to 70 per cent less ongoing lighting and heating costs

- Far quicker speed of construction

House size: 14.4 sqm

Bedrooms: 1

Heating: air to air heat pump

Ventilation: heat recovery ventilation single unit

Construction: timber frame

The build

Building my tiny house on wheels in Co Laois took 300 hours of skilled help, 150 hours of invaluable unskilled help from friends, and about 1,000 hours of my own amateur labour.

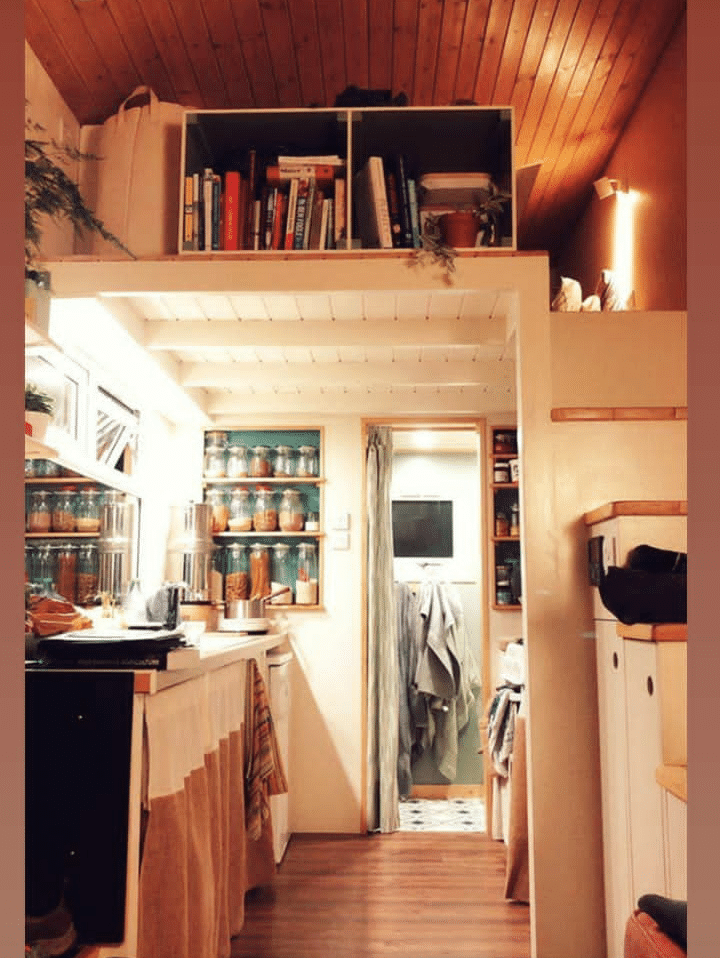

My tiny house is (externally) 6 metres long, 2.4 metres wide and just under 4 metres tall from the bottom of the wheels to the point of the apex roof.

It’s a timber framed construction built on top of a hot dipped galvanised purpose manufactured chassis, which I imported from Germany.

I used ‘smart framing’ (also known as advanced framing) for the timber studs, which is to use 3×2 with 24 inch spacing instead of more conventional 4×2/6×2 with 16 inch spacing. The scale of the construction allows for this safely. I clad the framing internally with 6mm CE2 ply and externally with 9mm CE2 ply. This gives the house its shear strength and is my internally finished wall.

A high performing thermal envelope was absolutely essential to me, as a building that can’t keep efficiently warm is simply not sustainable. I made it airtight and created a continuous insulation barrier on the external wall, floor and roof.

The floor and ceiling, which are made from 4×2 framing, have 100mm of stone wool insulation. The 3×2 studs have 70mm of high spec mineral wool insulation.

As most heat is lost through the stud framing, I wanted to create an effective thermal break. I glued 25mm PIR foam to the 9mm CE2 ply on the external wall, creating a type of Structurally Insulated Panel (SIP).

I cut every overlap of the PIR at a 45 degree angle on the table saw to avoid any pieces butting up or bending out (that would create a risk of heat leakage). Given that the PIR sheets are largely waterproof on their foil facing side, I taped over where they join with a waterproof tape to add an arguably unnecessary but low investment extra rain barrier.

I used a weatherproof membrane, for breathable waterproofing, followed by trapezoidal steel sheeting on the roof and three sides. The steel sheeting had lived a previous life as a cattle shed, and seeing how the landscape of Ireland is decorated with these monuments to agriculture, I wanted the house to reflect its environment somewhat. There’s really no material that’s more sustainable than one that’s reclaimed. The majority of the front of the house is clad in Siberian larch which I purchased from a great supplier in Cork. Garry delivered it pretty much the next day after payment, it was beautiful to work with, and has weathered nicely.

I designed an angle into the front facade as a visual metaphor. There is always another angle to a problem, another solution. The sun casts a shadow from nearby buildings, creating a second angle that I find really pleasing.

The windows and doors were all reclaimed and second hand, I got some real bargains online. The windows have been brilliant; the door has been a disaster. It opens in which was never my intention, but a friend picked it up and when it arrived, I just had to roll with it.

It’s been leaky, draughty and a real pain. I should really fix or replace it and it’s on the list. My search for a second hand, open out door in Ireland has so far proved fruitless in nearly two years. So the search continues.

Energy

Now living in Co Tipperary, I have no empirical data on energy efficiency but it’s the warmest house I’ve ever lived in. Designed to face south, with windows on the east, south and west, the layout maximises solar heat gain by tracking the movement of the sun.

My heating system is a 9000BTU air to air heat pump, which was cost effective and works incredibly well. As the name indicates, the heat pump heats up the air directly so there are no wet components. My energy is offgrid. I have a nine panel solar array, a 300Ah lead acid battery (weighing a whopping 300kg) and an incredible Swiss 3.5kW inverter. The hot water for the shower is powered by propane and from April until about November I cook on induction when we’re in the free energy season.

A back up petrol generator charges the house about once a week during the darker months from November to mid-March.

Setbacks

Taking on the design and build wasn’t all plain sailing, but nor was it impossible. My amateurism certainly slowed things down and where I chose to build, in a rural location, created a huge time suck of gathering materials as most of them weren’t available locally.

I also came across issues using Sitka spruce, which was poor quality. My heat recovery ventilation system is suboptimal and I have ongoing moisture management issues but the house is so small, opening the windows for purge ventilation does the job for the moment.

The case for tiny living

If I, a person with no real construction experience, could be the main labourer and project manager and complete an entire home in about four months, imagine what could be achieved by an industry of skilled professionals who really know what they’re doing.

The reality is that tiny houses are (surprise!) tiny. It’s a lifestyle choice that involves fewer material possessions and a more tailor made, person-centric design aesthetic. From my own experience, the switch has been easier and more liberating than I initially imagined.

One of main lessons I’ve learned is that anything more than what’s needed is a waste. A version of Parkinson’s law dictates that the more space you have, the more superfluous things you will find to fill it. Storage gets crammed with clutter and things that, if we really had to choose, we could live without.

I have no illusions that tiny living would not suit everyone, but for those that it could, it is a viable and accessible alternative to traditional housing that certainly merits exploring.

For more about Paul’s tiny house go to smallchange.ie or check out his Instagram account: thesmallchangemovement

Suppliers

Chassis

Manufactured by Al-Ko Kober

Siberian Larch

QEH (Quality European Hardwoods) in Cork

Insulation

Rockwool and Isotherm

Membrane

Tyvek by Dupont

Windows and doors

Second hand from adverts.ie and donedeal.ie

Solar system

Second hand mostly from ebay.ie