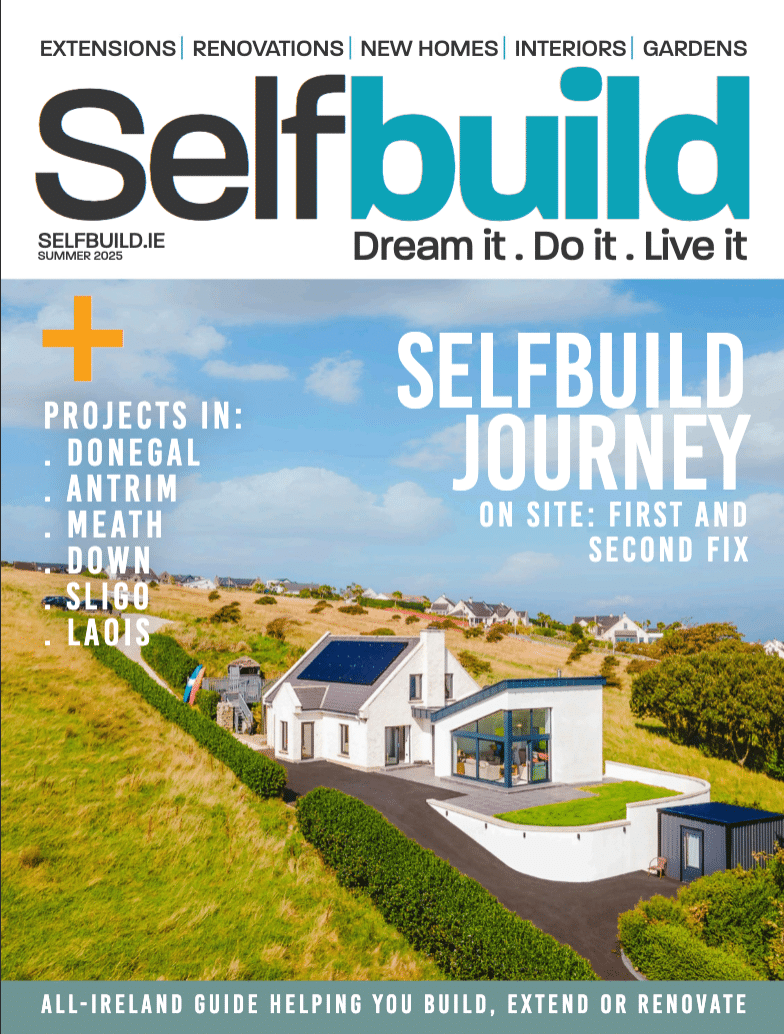

This Co Antrim project shows how a sympathetic modern extension can enhance the appearance of a vernacular thatched home.

In this article we cover:

- Renovating a 200 year old Grade II listed building including internal reconfiguration

- Working with building control and NIEA Built Heritage

- Designing a modern extension alongside it

- Linking old with new while avoiding cold bridging

- Choice of materials

- Timber components internally and structurally

- Project management details and how the extension was built

- Troubleshooting on site

- Details of professional garden design

- Heating system upgrade

- What they would change

- Specification, timeline and supplier list

- Floor plans and professional photographs

Site size: 1 hectare

Original house size: 160 sqm /Extension size: 52 sqm

Construction method: timber frame

SAP rating (EPC): 52 (E)

Conservation architects will tell you the best way to preserve an historic building is to live in it; the occupier is likely to spot and deal with things like leaky downpipes early on, thereby avoiding irreparable damage.

Taking things a step further, old houses often require alterations and extensions to make them work in a modern context. You don’t want to create a pastiche that will detract from the original, nor do you want to build something that ends up looking like it’s been planted there by aliens.

The answer, for Desmond and Jeannine Barrow of Co Antrim, consisted of a harmonious blend of natural and modern materials.

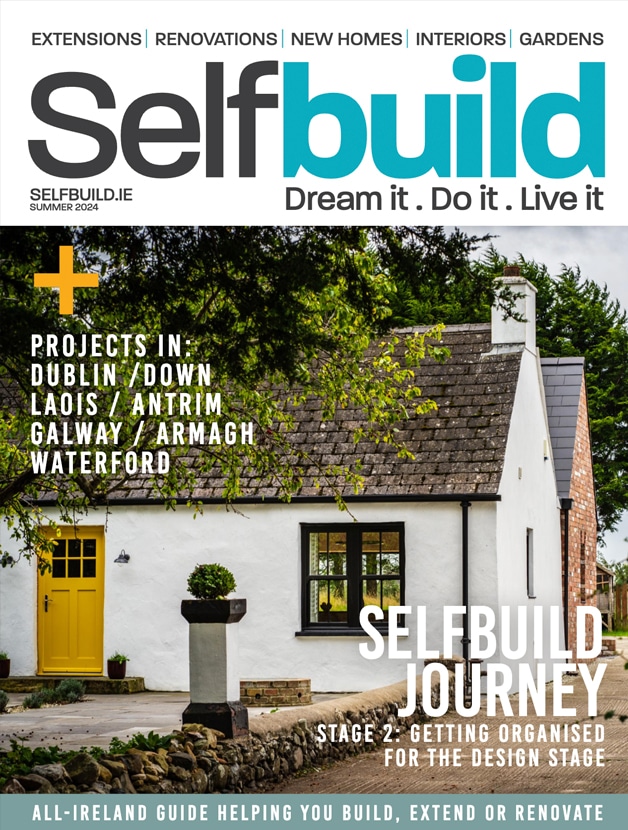

This 300 year-old thatched cottage has been their home for over three decades. “Growing up here, the house always felt like a part of the family,” says their daughter, and architect, Aisling. “We’re all very attached to it.”

And oftentimes with attachment comes a fear of loss. “We watched our children grow up in this house so it’s full of memories. It can be hard to let go of those, and accept that your home needs to be altered in some way,” says Jeannine. “But we had outgrown the house and knew that some modernisations were long overdue. We also really wanted a room from which we could enjoy our garden better all year round.”

Marrying old and new

It was a logical choice for Jeannine and Desmond to ask Aisling to design them an extension. At the time she was still completing her architectural studies in London and Cardiff, and so they had consulted with a few more experienced architects before she voiced her interest in taking on the project herself.

“We started by visiting the SelfBuild show to get some ideas and talked to a few architects,” says Desmond. “We had some difficulty coming up with a design. Most of the suggestions were quite traditional and conservative in nature. Aisling had something quite different in mind; we agreed with her that a modern extension would make an exciting addition to the cottage.”

“I love the character and the quality of workmanship of old buildings,” says Aisling. “The simple shape of the extension echoes the linear, vernacular form of the original cottage. But rather than stone and thatch, the new addition is made from oak, cedar and lots of glass.”

“I also drew inspiration from the simplicity and materiality of Gumuchdjian Architects’ Think Tank building in Skibereen, which is made from iroko and glass. It’s got a strong sense of the vernacular and is modern at the same time.”

Much wood used in construction nowadays is quickly grown and kiln dried to avoid the issues of cracks and shrinkage. “Building with green oak makes a virtue out of one of these properties because as the elements dry, they bond together really strongly,” says Aisling. “They still shrink and crack, though, which could be problematic with so much glazing, so we didn’t use green oak but rather air dried, which means there was less movement.”

“We chose oak for its authenticity and timelessness,” adds Aisling, “making sure it was sustainably sourced, as was the native character grade oak used for the external cladding, internal roof and wall surfaces.”

As is often the case with exposed timber frame, what starts off as a structural element carries through to the aesthetic of the interior. “The floor is engineered wood with underfloor heating,” says Desmond. “It was recommended to us not to use solid wood over underfloor heating, but we were still able to get an oak finish. The new door is oak as well and the new floor in the cottage downstairs also replicates the oak colour we have in the extension.”

The design process began four and a half years ago in 2009, and the build kicked off in the summer of 2010, to be completed a year later in 2011. The garden and the floors, meanwhile, were finished in 2013. “We initially put carpet in the cottage but always with the intention of replacing it with solid flooring eventually,” says Desmond. “Changes take place over a period of time.”

Glass links

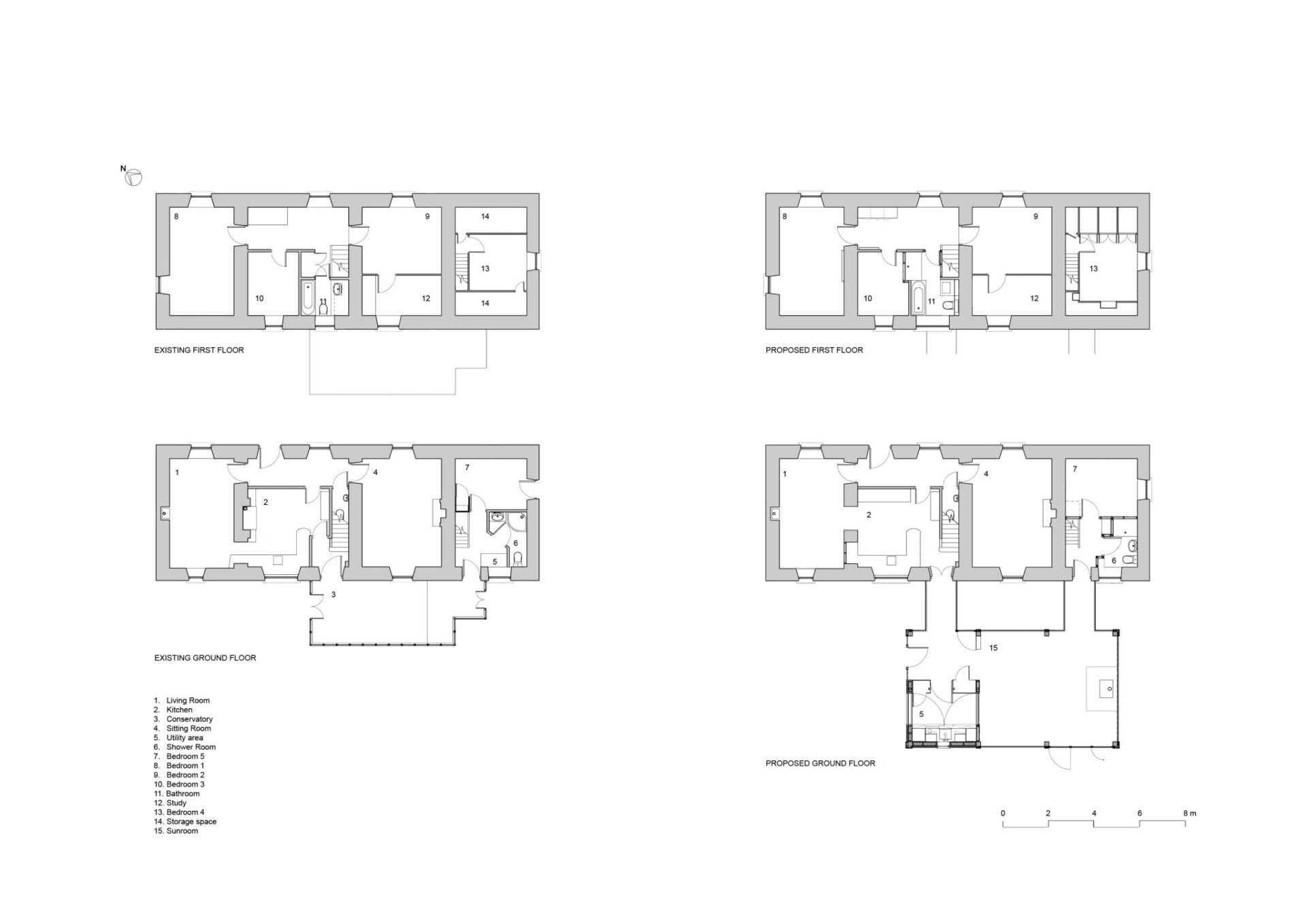

“We wrestled with how to reconfigure the design, as we previously had a 1980s single-glazed conservatory at the back of the house, which we wanted to replace,” adds Desmond. “The conservatory was the only link between two parts of the house – the main cottage and a former cattle shed that we had converted into two small bedrooms and a utility area and shower room in the 1990s. We also wanted to free up some space in that part of the house by relocating the utility to the new extension.”

A lot of consideration was indeed given to the link between old and new, not least because it would have a strong impact on the exterior appearance. “The real challenge was how to connect a modern extension to the old house without compromising either of them. This was all the more difficult because we needed to access the extension from two different parts of the house.”

“Then I had the idea that the extension could be separate from the house, but with two glass links connecting them, creating a small, enclosed courtyard between them,” adds Aisling. “Cold bridging and penetration of damp was avoided at the junction of the glazing to the original stone walls by cutting a slot into the stone, into which a vertical DPC and slivers of insulation were inserted.”

“The extension and the glass links are very warm thanks to the underfloor heating,” adds Jeannine. “We commissioned an Irish artist to create a sculpture for the courtyard between the links. He came to the house to get inspiration and made us an eagle to place between the two.”

The third ‘glass link’ in the design consists of the minimalist laundry room. “We wanted a utility room but the ideal position spoiled the views of the lough,” says Desmond.

“To get around this, I decided to conceal the units within a linear timber box,” explains Aisling. “When not in use, the box is ‘closed’ and two large windows allow you to gaze from the sunroom through the space to the view of fields and lough beyond. When the utility room is in use, large moving walls/doors open to reveal the units, and in so doing they cover the windows, creating an enclosed utility room.”

“Being able to see the lough is wonderful,” enthuses Jeannine. “The sunroom is so bright and the light within it changes with the seasons and the time of day. It feels very spacious and like a part of the garden, which is something you never felt within the rooms of the old cottage which, with their small windows, are quite separate from outside.”

The building certainly couldn’t sit any better in its landscape. “The oak frame and cladding can be seen from the outside and the cedar shingles on the roof soften the impact of all the glass,” says Desmond. “You can see through the sunroom from the outside, right through to the cottage.”

Existing cottage

Since refurbishing the cottage was at the core of the brief, a conservation architect was brought on board to provide expertise in working with old buildings, monitor progress on-site and act as a mentor to Aisling. “As this was my first independent project and it was before I had fully qualified as an architect, he provided support by checking my drawings and answering my questions when I needed advice, especially when dealing with the old house,” she says.

The cottage is a Grade II listed building, which led Aisling to involve NIEA Built Heritage from an early stage in the process, in order to take any concerns they might have into consideration and ensure the job was carried out with sensitivity towards the cottage’s historical value. NIEA Built Heritage are consulted by the Planning Service when an application is made for work to listed buildings. “They were very enthusiastic and supportive about our ideas, and we had no problems getting planning permission for the extension,” adds Desmond.

“Building Control can be challenging when carrying out work to a listed building. For example, regulations that stipulate you must add insulation to existing external walls when you re-render them are very problematic in a historic building if you don’t want to alter its appearance too much,” says Aisling.

“Again, we worked closely with the building control officer and he was willing to show some flexibility. We took additional energy conservation measures elsewhere in the old house to compensate for the lack of insulation to the walls, for example adding insulation to the floors.” The thatch roof also provides significant insulation as it’s made of reed.

In addition, the existing cottage was partly reconfigured. “The kitchen is the central part of the house and at its core we had an oil fired central heating range cooker,” says Desmond. “It tended to be on for around eight months of the year, and while wonderfully cosy, it consumed a lot of oil and was not a very efficient form of heating. We replaced it with a high efficiency oil-fired combi boiler in the new utility room.”

The cosy old range may have been removed from the kitchen but at the heart of the new sunroom is a large wood burning stove, which provides a similarly warm focal point.

“We were committed to a sympathetic restoration so we sourced a thatcher and a lime plasterer,” says Desmond. “We wanted to remove the existing, non-original cement harling, which didn’t allow the building to breathe, and replace it with lime render. The original, single-glazed sash windows were overhauled and draught-proofed, too, which has made them more energy efficient and a lot less inclined to rattle.”

“Because the building is listed we couldn’t change very much on the outside,” adds Jeannine. However, they were able to replace a non-original, slate-roofed dormer at the back of the house with a thatched eye-brow dormer which is more sensitive to the traditional style and, being wider than the previous window, has the added benefit of allowing more light into the bathroom.

“When we bought the house in the early 1980s, we moved the bathroom from a rear lean-to, which we demolished, to where it is now upstairs. When we were carrying out this recent work, we took the opportunity to make it bigger by eating into the adjacent bedroom to make room for a separate shower and bath. The rearrangement has made it much more functional,” says Desmond.

“We’d simply grown out of the old house, and some alterations were long overdue,” adds Jeannine. “The house had served us well, bringing up our family in it, but it was getting a bit tired.”

“It’s a lot better now although we spend most of our time in the extension! We didn’t expect that to happen at all, we built it thinking we’d use it mainly for family occasions and entertaining, not for everyday living. It’s so comfortable and the views are so enjoyable it’s hard to keep away from it.”

“We spend our time there from breakfast to evening,” adds Desmond. “It just has such a lovely atmosphere. Anyone who comes to the house is drawn to that space, it’s so calm.”

In the thick of it

In a way this project was the ideal commission for Aisling; she’d grown up in this house and couldn’t know her clients any better. However mixing business with pleasure can have its downsides.

“It was hard not to get a bit obsessed with the project,” she says. “Even on holidays or family occasions, the conversation often drifted back to the house! It was enjoyable but all-consuming.”

It was Aisling who located an oak framing company to not only to supply the timber but also to detail and construct it. Another contractor and project manager was brought on board for the cottage renovation.

At slightly over one year, the construction process took longer than Desmond and Jeannine had initially expected. This was in part because the job grew in scope as it progressed, when they decided to make additions such as digging up the clay floors in the cottage to add insulation and covering it with concrete. “The construction was also more complex because we had the involvement of a lot of different people, including two contractors and the two architects,” adds Desmond.

“Aisling moved to Scotland for a job shortly after construction began, so her involvement was mainly by telephone. With hindsight, it might have been easier to appoint one project manager to oversee the entire project, including construction of the extension and alterations and conservation work to the old cottage. Then we would have had a single point of contact which might have made life easier instead of trying to coordinate between so many different people who were responsible for different elements of the project.”

“Another thing I would change if we did it again is that I would install underfloor heating in the cottage ground floor that we replaced and insulated,” adds Jeannine. “It would have avoided the need for radiators which take up precious wall space in the small rooms.”

Seeing it from within

The new sunroom is so transparent, the Barrows felt they could use the help of a landscape architect. “We got him on board in 2013 and just asked him to be creative,” says Jeannine. “We didn’t give him an exact specification and he didn’t give us full plans, we worked on the fact that we liked his approach. He worked on our neighbours’ garden, and we loved it.”

“One of the reasons why we needed to get him in was that we were late in identifying the issue that the water table was high, so he was able to deal with that in his design.” He created the patio area with surrounding pond and mound, as well as the wildflower meadow.

The lighting was also carefully devised. “Outside a series of spotlights highlight the house. Inside you get an antique effect with some signature pieces, such as the pendant light in the sitting area,” says Desmond. “We have wall lighting and lamps for subtle effects.”

By using their existing furniture and complementing it by a locally sourced burred elm shelving unit, the Barrows were able to give the sunroom a ‘lived in’ feel. The green oak cracks as it ages, which immediately adds character.

“The roof’s cedar shingles will grey with age, as will the thatch, so they will complement each other nicely,” he adds. Zinc was used in the glass links, for the roof and gutters. “Downpipes can look a bit unsightly so I suggested we put in chain drains to take the rainwater off the links. It was a way to make something functional a bit more interesting,” says Aisling.

“At night we thought we might feel exposed because we have nothing to cover the glass,” says Desmond. “We ignored convention and didn’t install blinds. But in actual fact the darkness acts like a sort of curtain – you see yourself and the room reflected over and over again in interesting ways. We’re on one hectare of land, with lots of mature trees and an indigenous woodland that was planted 25 years ago, so there’s no worry of being overlooked.”

Guided by the love and attention of the family that has been taking care of it for the past 30 years, this old cottage was given a sympathetic yet modern facelift – one that will ensure it will continue to be lived in and cared for into the foreseeable future, if not for centuries more.

Spec

Construction: timber frame (air dried oak)

Insulation: rigid phenolic insulation boards throughout

U-values: walls 0.16 W/m2K, floor 0.18 W/m2K, flat-roofed links 0.14 W/m2K, main roof 0.19 W/m2K

Windows: aluminium-framed 70mm profile double glazing with 16mm argon gap and low-e coating, U-value of units 1.77 W/m2K

Suppliers

Architect: Aisling Shannon Rusk, Belfast, of Studio idir

Conservation Architect: Denis Piggott, Downpatrick, Co Down, tel. 44830800

Structural Engineer: White Royall Dixon Engineers Ltd, Southampton, UK, whiteroyall.co.uk

Landscape Architect: Noel Sweeney, Plotscape, Craigavon, Co Down, mobile 078 89082913, plotscape.com

Sculptor: Ronan Halpin, Achill, Co Mayo, mobile 087 277 0409, ronanhalpin.com

Joinery for doors, timber window and utility room joinery: R.H. Joinery, Coleraine, Co Derry, tel. 7035 5431, rhjoinery.com

Timber: Oak sourced from S. H. Somerscales Sawmills Ltd, UK; for the shelving unit L. E. Haslett & Co Sawmill, Clogher, Co Tyrone, lehaslett.com; Western Red cedar singles for roofing sourced from Canada via Silva Timber Products, UK, silvatimber.co.uk.

Aluminium Glazing: Schüco (schueco.com) supplied by Glazing Design Systems, Banbridge, Co Down, tel. 4062 3866, glazingdesign.co.uk

Insulation: Kingspan Kooltherm, kingspaninsulation.ie

Wood burning stove: 6kW Scan 50, scan.dk

Thatching: Peter Brugge, Master Thatchers (North) Ltd, Cheshire, UK, mobile 07860 869 481, thatching.net

Lime Render: Barnie McKay, Antrim, mobile 07710612574

Sash window renovation: Ventrolla, Belfast, tel. 0800 378 278, ventrolla.co.uk