Find out what changes Tomás O’Leary made to his home, which was the first Passive House certified self-build not only in Ireland but in the English-speaking world.

But the Passive House method had been tried and tested in Germany so, undeterred Tomás set about replicating it here. This despite the fact that Tomás had to import all the materials for his selfbuild, including the triple glazed windows, as none of them could be sourced in Ireland.

Passive house pinoneer overview

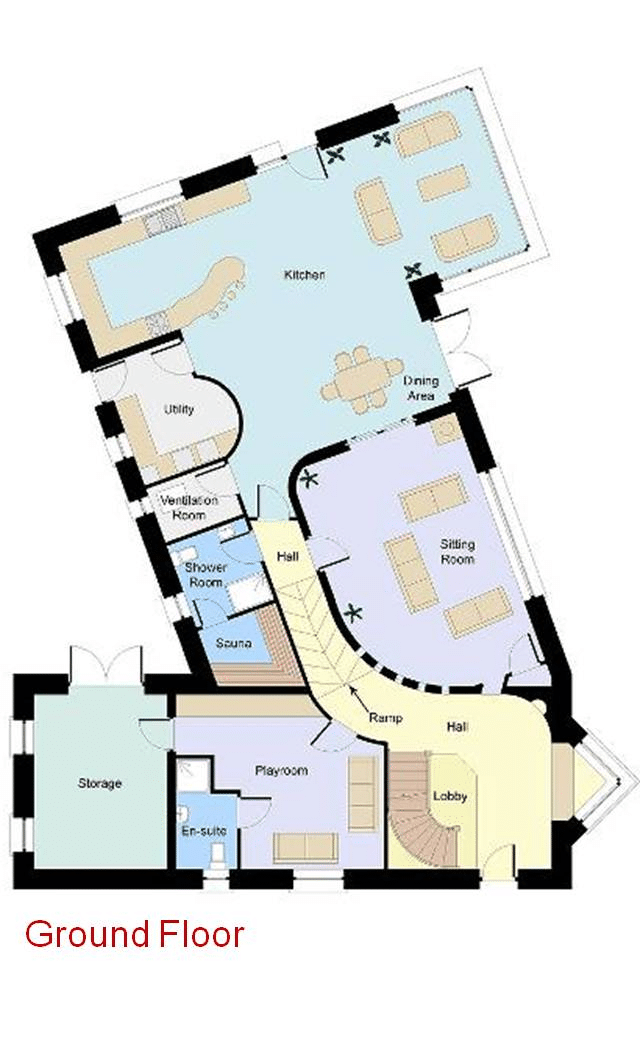

House size: 350 sqm

Cost of heat pump upgrade and radiators, including remedial work: €12,000

“It’s a method that’s quite straightforward to replicate here and it’s really gained in momentum over the past 10 years. I actually never expected the Passive House standard would take over my life in the way that it did,” says Tomás whose architectural practice MosArt established the very successful Passive House Academy in 2009 and more recently, in 2016, the Nearly Zero Energy Buildings Resource Agency (NZEBRA).

No performance gap

“The Passive House standard aims for a very high level of insulation and airtightness coupled with a heat recovery ventilation system,” explains Tomás. “The layout (compact footprint) and orientation (how the rooms face the sun) also play an important role.”

What’s reassuring to Tomás is that 14 years after moving in, the house is performing exactly as had been predicted by the Passive House energy model in 2003.

“We just got the results in from Ulster University, which has been monitoring the energy use of our home over the past year, and the house is performing exactly as the Passive House Planning Package said it would. It’s extremely gratifying to see that there is no performance gap.”

A performance gap can arise for many reasons, one of which is the energy model used which might underestimate the heating energy demand of the dwelling, another is poor construction – the key to a low energy build is for there to be rigorous attention to detail on site.

It can also be due to not having perfectly detailed the specification for the house’s exact site conditions, which can vary greatly in Ireland with its multitude of microclimates (see Weather forecast, right). Thankfully none of these were issues for Tomás.

Wood pellets for the first eight years

“We had installed a wood pellet boiler, which we felt was the environmentally sound solution because back then heat pumps weren’t as widely used and available as they are now. This choice resulted in some level of upkeep between having to top it up by hand and emptying the ashes,” says Tomás.

“Passive houses typically have a constant trickle of heat being emitted; with the stove we turned it on and off because we didn’t want to leave it running unattended. It’s a combustion system, so at night we didn’t have it on nor did we during the day when the house was empty.”

“It would take an hour for the pellet boiler to come to working temperature, which seemed like a long time. I suspect there were some inefficiencies in the length of pipework runs and insulation levels and there may also have been a lack of maintenance issues on my part over the years,” confides Tomás. “This had a knock-on effect on the comfort levels provided as the heat distribution throughout the house wasn’t even.”

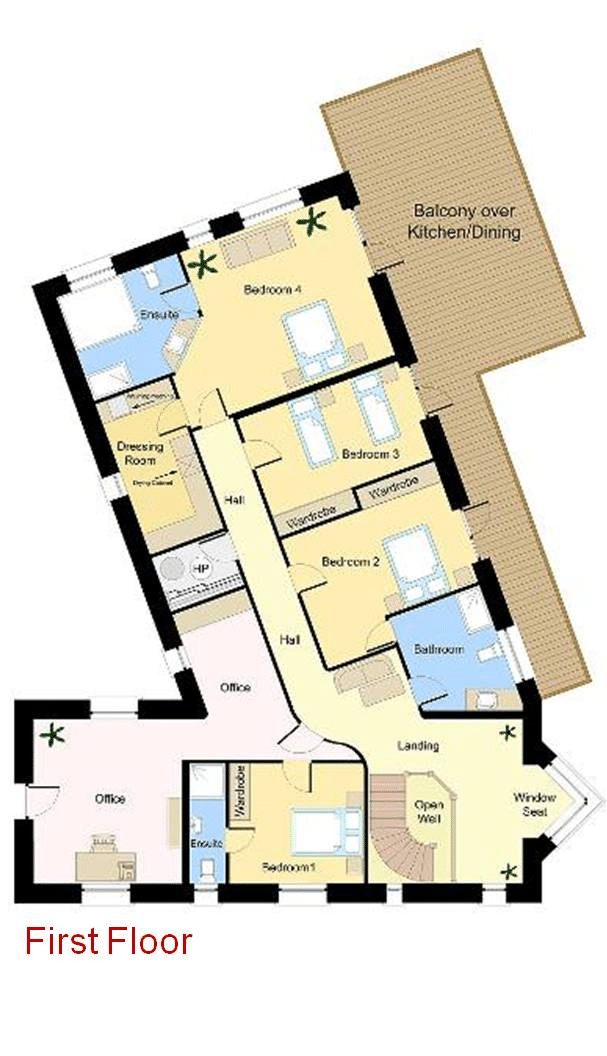

Even though the building had been designed to be as compact as possible, the layout dictated that a portion be north facing. “One bedroom on the north facing aspect, which was unoccupied and which had no exposure to sunlight in the winter, was slightly cooler that the rest of the house,” explains Tomás. “This part of the house protrudes with three external walls – not an optimal design with respect to form factor.”

The 10kW wood pellet boiler, which at the time cost €11,000, emitted 80 per cent of the heat in the living room and 20 per cent went to the hot water tank.

Thanks to the quality of the construction, the heating bills for the year were low. “We used one and a half tonnes of wood pellets, the equivalent of about €400 a year covering both heating and domestic hot water. But overall, considering the capital cost you could say it was an expensive experiment,” tempers Tomás.

Heat pump for the past three years

In 2014 we ended up getting rid of the wood pellet boiler and retrofitting an 8kW air-to-water heat pump with fan assisted radiators as heat emitters,” he says. There are four radiators downstairs and just two upstairs, one of which is in the above mentioned north facing bedroom. The heat pump also supplies the hot water tank.

“What’s wonderful is how evenly spread the heat now is around the house. That and the fact that we have no solid fuel – there’s no need to store it or haul it. It’s just so much more convenient and more comfortable.”

The fan assisted radiators have a low and high speed, as soon as the temperature drops the fan kicks in to bring the room back to temperature.

“Even though the wood pellets per kilowatt hour are cheaper to run, with electricity being the most expensive source of energy, the comfort factor is well worth the extra couple hundred euros a year* it theoretically costs me to run the heat pump,” concludes Tomás.

*The heat pump controls indicate it consumed 3,550kWh in the past year. (This was confirmed by comparing electricity usage during the days of the pellet boiler, which was averaging at about 7,500kWh/ year, to the electricity bills of the past 12 months with the use of the heat pump which recorded a consumption of 10,500kWh/year, 1,400kWh/year of which was supplied by the second-hand PV panels installed on the house two years ago.) At an average cost of 23.4c/kWh (SEAI 2016, Band DC) the cost of heating and domestic hot water (combined) for the heat pump was approx. 3,550kWh/yr x €0.234/kWh = €830/yr. This compares to the approx. €400 a year spent on wood pellets for the boiler.