You need a ventilation system to get fresh air into your home, so what are your options and how do they stack up?

In this article we cover:

- Comparison chart of the most common ventilation systems available in Ireland

- Explainer of what each ventilation system consists of

- What are pressure differentials and why they matter

- Illustrations explaining pressure differentials

- Why every home has some form of ventilation and the need for controlled ventilation

I was first introduced to the passive house standard in 2013 and went on to become a certified passive house designer. Since then I’ve been involved with a range of certified passive house projects.

And from experience, there’s always one point of contention. The one area that divides opinion, and that seems to be open to interpretation in practice, is ventilation. Yet ventilation has much more significance than many appreciate, for health and wellbeing.

Most of this opinion piece is taken from a chapter from my own PhD research where I monitored over 100 certified passive house homes for indoor radon concentrations. As part of this research, I looked at the various ventilation systems within the Irish and UK marketplace.

[adrotate banner="58"]Ventilation and indoor air quality have been an issue of significant debate over this past decade. Many in the industry have concerns about the design, specification, installation, commissioning, and operation of balanced mechanical ventilation heat recovery systems (MVHR).

What became apparent from my research is that other modes of ventilation such as natural ventilation strategies aren’t studied nearly as much.

Yet the traditional and still the most common ventilation strategy implemented in Ireland and the UK is natural ventilation, also referred to as uncontrolled ventilation. On new builds, this method of ventilating goes against building an airtight house in the first place. Simply because natural ventilation relies on draughts for fresh air, which lead to excessive heat loss.

The other common ventilation strategies employed are all under the auspices of controlled ventilation, most of them centralised, and include the following.

Positive Input Ventilation (PIV) and Mechanical Extract Ventilation (MEV)

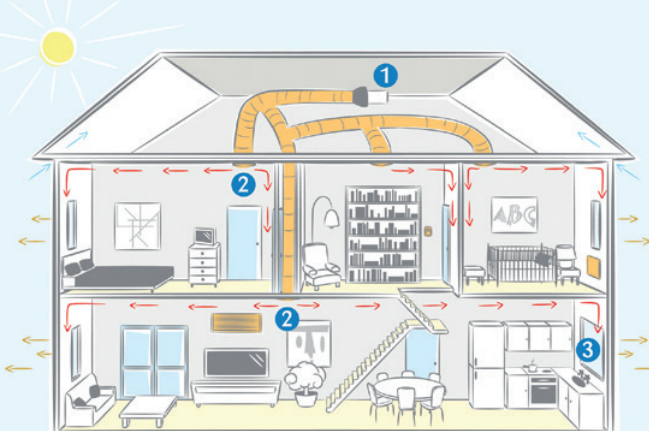

PIV is mostly installed into existing homes. The system supplies fresh, filtered air to specific rooms from the PIV unit, which is normally located in the attic, with ducting and ceiling mounted valves.

The main console pulls air from the attic space or from outside, filters it, and supplies it into the dwelling, thus applying a positive pressure on the building envelope driving stale air out through any gaps in the thermal envelope, i.e. through vents, gaps around window sills, etc.

MEV is almost the opposite of PIV. It is a central fan that extracts stale or moist air from rooms of high humidity such as the bathroom or kitchen. This creates a negative pressure, which theoretically draws fresh air evenly into the property through the envelope of the building.

Balanced Mechanical Heat Recovery Ventilation (MVHR)

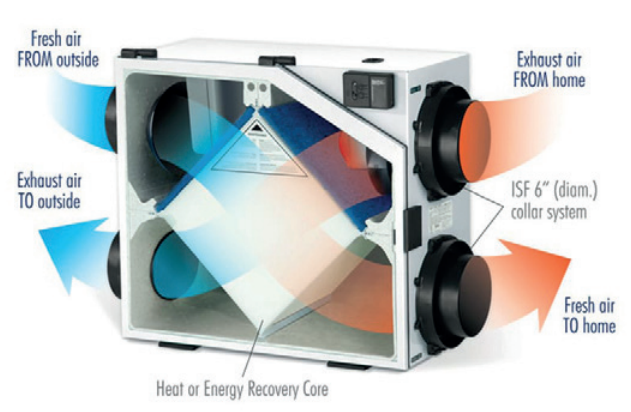

MVHR consists of two fans which run independently, conducting supply and extract airflows simultaneously. The extract duct and fan will extract stale, humid air from the wet rooms (bathrooms, kitchen, utility, etc).

This stale air is extracted through a heat exchanger where heat is ‘recovered’ before it is discharged outside the house. The second fan draws fresh air from outside, which is then filtered with an F7 grade filter to remove any pollutants, airborne allergens, and this air then passes over the heat exchanger to heat the air, and thus supply pre-heated filtered (G4) fresh air to all the living areas and bedrooms.

Demand Controlled Ventilation (DCV)

DCV is a modulating extract system that uses smart sensors, controllers, and ventilation fans. These sensors continuously measure and monitor indoor air quality and provide real time feedback to the controller.

The controller sends the sensor information to the fans, adjusting the rate of ventilation according to the environment in each room. These extract fans are placed in attic spaces or utility rooms and are connected via ducting to extract valves in wet rooms (kitchen, bathroom, utility).

Air comes into the house through humidity sensitive wall inlets in the dry rooms (bedrooms, living rooms). The system constantly varies its operation to match the behaviour of the house.

Pressure Differentials

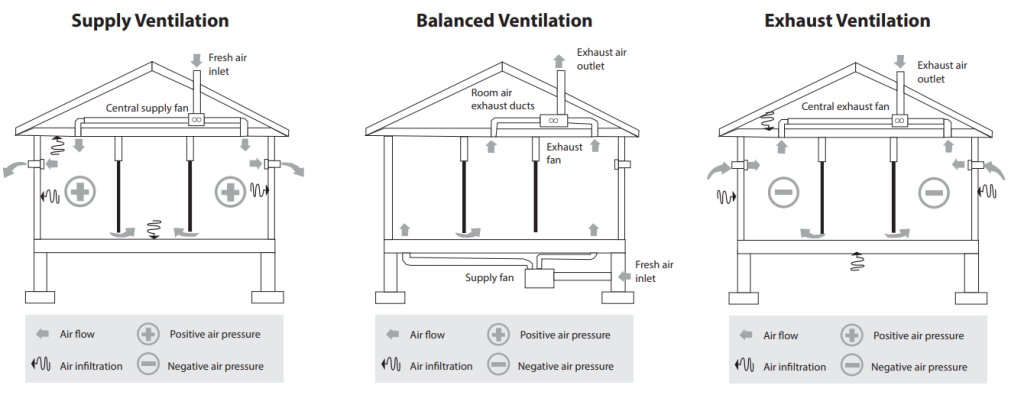

Each of these mechanical systems will induce either positive or negative pressure differentials. Negative pressure will potentially promote the ingress of leakage air flows into the building. On the other hand, positive pressure exerted will help guard against infiltration of air.

The downside is that any moist interior air is typically forced out through cracks and gaps in the building envelope, where it may contribute to moisture buildup. This could manifest as interstitial condensation, which is water that forms between construction layers. Because it’s not visible, significant damage can occur before noticing.

A balanced MVHR offers flexibility in this respect because it has two fans, so the speeds of these fans can be adjusted and balanced.

However in practice, MVHR systems have a slight pressure differential either positive or negative.

The certified passive house standard mandates during the commissioning of these systems that the imbalance be less than 10 per cent. Best practice is less than 3 per cent which is almost neutral in terms of the pressure differential.

This is why correct installation and good design practices are significant as they affect the pressure differentials and potential influence of air infiltration. A requirement for certification is evidence of final commissioning including balancing of the fans to within 10 per cent.

Ventilation System Risk Matrix

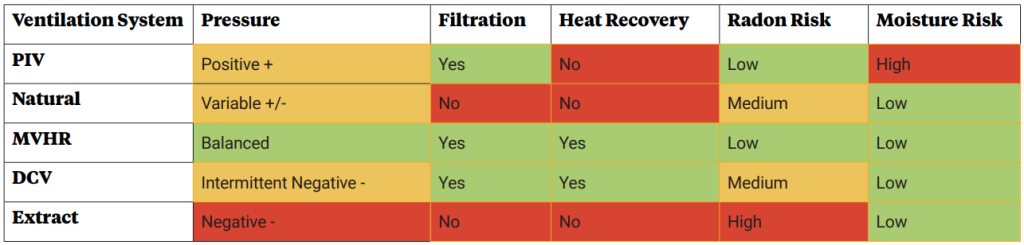

The table above is a conceptual risk matrix to illustrate the differences in typical controlled ventilation systems in the Irish and UK marketplace and the corresponding influence of pressure differentials that pertains to radon, moisture risk and air infiltration.

This also includes filtration, which is important as radon progeny are tiny solid particles that, if in the air when radon decays, can attach to dust and other particles and move with the air. Radon progeny that are attached to dust can be removed by air filters. The risk levels depicted above are indicative based on the corresponding pressure differential and the filtration level.

My hope is presenting this conceptual risk matrix is that it will provide further insight into the various systems available within the Irish and UK marketplace. Based on my research, balanced MVHR systems when installed, designed, and commissioned correctly offer clear benefits over the other systems.

On the topic of installation, design and commissioning, the certified passive house standard offers a quality control framework. Checklists and guides are available through passipedia.org.

In my opinion, this passive house framework is one of the key reasons the passive house standard is so successful in producing buildings which perform both in respect of heating demand and indoor air quality without the performance gap, which many other buildings unfortunately do suffer from.