Orientation is about where to position your house, how to angle it and how to make best use of the site you have.

Your architectural designer will help you decide the orientation of your home – that is, where to position it and how to angle it on your site. This will be done in relation to the sun, as well as the views, but there are even more fundamental issues to consider.

In this article, Art McCormack FRIAI of Mosart covers:

- Optimal site size and width

- Optimal site conditions, i.e. access, topography, etc.

- How to make the house energy efficient: house size and location on the site

- Optimising views and issues with cut and fill

- How to make the most of the views and sunlight

- Which way the rooms should face

- Working with the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP)

- Whether to buy a site with planning permission or not

- How to use trees and shrubs and what species to plant on your site

- How much lawn to include, layout suggestions

I’m currently site hunting, what features should I look for?

There is no perfect site but if you plan to build a house out in the countryside, the rule of thumb is to look for about three quarters of an acre.

This is to accommodate the house, a well, recreational areas, a fruit and vegetable patch, car park and garage/outbuilding, but also the inevitable but hidden septic tank with its percolation area. Inability to provide adequate space for the latter is literally a show stopper – planning will not be obtained.

Where space is restricted, it’s worth exploring compact systems involving secondary treatment that can be more efficient than traditional systems and may limit the area required for percolation.

There are, however, fundamental parameters for drainage systems generally requiring certain setbacks from the site boundary as well as distances from the house that might be partially determined by the site shape and proportions.

A safe bet in this regard would be to buy a site that already has outline planning permission where a drainage or site suitability assessment has been carried out with a system designed to comply with best practice standards and regulations. But these are not that commonly available.

Safe access from the site to the road and providing good sight lines will also be required. A typical set-back distance for assessing road visibility along these sight lines is 2.5 metres from the road edge, which corresponds roughly to where you would sit in a car with the front bumper back a bit from the road.

An integral part of both the site and sight line assessments is a topographic survey, concerning site levels or contours. Based upon this survey, the planning authority will determine the feasibility of the proposed development regarding drainage and road access.

Each site is unique and solutions can be found for most, provided sufficient area is provided. Sites of limited area but which are narrow or broad will require greater skill in fitting in all the required functions in a meaningful and useful manner. This is often most effectively achieved with the input of a design professional, such as a landscape architect or architect.

How might I best use trees and shrubs?

Generally speaking it is a good idea to retain existing trees and hedging, not least because they are likely to comprise native or semi-native species. At the very least, keeping what’s there will prove sustainable, preserving biodiversity and enhancing wildlife, especially in the case of hedgerows. This approach is also more likely to ensure good integration of the new development into the surrounding area, particularly if rural.

There is an understandable temptation to clear a site completely, especially along the road edge and then to introduce ornamental species that are not found in the vicinity of the site. However, you are more likely to conform to expectations of the planning authority by retaining as much of the existing roadside hedgerow as possible, thus reflecting the context. These are characteristics of traditional rural Ireland and can help to knit the new house into the surrounding landscape.

As a rule, avoid creating a suburban type boundary in rural areas. For instance, pink cherry trees in Spring will look out of place whereas native or semi-native species are usually preferable and appropriate. Notwithstanding, adjustments will be required to the roadside boundary on either side of this access point in order to achieve the necessary sightlines.

Mature hedges and trees around the site can create wind breaks, providing some shelter and helping to reduce heat loss from the house. Whilst this pertains to both evergreen and deciduous trees, the former may prove a critical impediment to solar gain, which would be especially problematic during the winter if located to the east, south and west of the house.

Deciduous trees to the south, however, especially those which are light in form (without dense branching and foliage), may prove less of a problem as they can create dappled light and shade during the summer but only minimal impediment to solar gain during the winter.

For example, the common ash tree is light in form, though as a fairly large tree would need to be set back from the house so as not to become overbearing, whereas mountain ash, also light in form but smaller, could be at a closer distance.

If clearing trees, be selective as some may be retained to frame a view. Of course, you can always plant new trees so as to achieve the same effect. Still, regardless of your fondness for trees, as a rule it is better to avoid building the house too close to them, not just because the roots could apply pressure directly to the foundations and floor, but also because a species like willow can draw moisture from the ground which could undermine these sub-structures.

How about hard and soft landscaping?

It is worth giving careful consideration to the extent of lawn you actually need or would like. I often wonder whether this inclination is ingrained, deriving from our ancient ancestors who cleared the land for tillage farming.

While large expanse of grass may seem to be the norm, I would always try to imagine alternatives, especially those that will save on the time and energy you otherwise would require every week throughout the summer in mowing operations.

Instead you could plant areas of shrubs and trees that cover the ground. Structure them in order to produce a more interesting, spatially and texturally, outdoor space. Perhaps layer areas of the garden so that some are subtly screened in whole or in part and the eye can both wander and wonder, resulting in a certain sense of mystery and intrigue.

Such a creative and playful approach generates an excitement and curiosity which are experiences we humans actually need. The likes of clear stemmed and multi-stemmed birch are very effective in producing a partial screen through filtered views.

Hard landscaping should also be used wisely; too much tarmac for instance, on a rural site, especially if wrapped around the house, can starkly disconnect you from the garden.

The practice of encircling the house in tarmac and concrete paths is in fact all too common. As a result houses often appear as if dropped by helicopter, completely detached from their context.

I’d advise minimising the extent of hard surfaces immediately around the building, instead bring planting and lawns right up to the walls to help you achieve a ‘soft landing’. Adequate car access can be achieved with driveways and carports which are visually shielded from the house.

What about the size and depth of the plot? Size and depth of house?

The preferred proportions of a site depend, for instance, on the location of car parking, on the one hand, and where you intend to position the main living rooms and contiguous outside spaces, such as patios and lawns. You need to plan these carefully. A narrow or shallow site will pose a challenge to the designer, but one that can give rise to interesting results.

Such proportions may also determine the scale of the house itself. From an energy point of view, the more compact its form the better the energy performance is likely to be. Just compare a fist to an open hand with fingers outstretched – which retains heat more easily?

Your designer or BER/EPC assessor could help here, aiming for a surface area-to-volume ratio of around 0.7sqm per cubic metre. A cube is the most energy efficient to heat but no one will actually build a house like that.

Indeed, there may be reasons to produce an elongated form or one with projections, but at least be aware of the need to consider the ultimate energy balance of the house an how to compensate. That is certainly possible.

What should the orientation be for my new build?

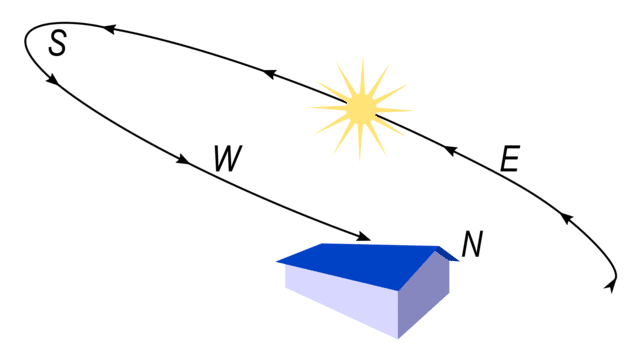

By and large, it is ideal to position the living and bedrooms so that they face south in order to maximise solar gains and place service rooms and circulation areas, such as halls, corridors and stairs, to the north. This is not always possible, of course, and you can adapt your design accordingly without compromising on the solar gains.

Similarly, the ideal position of a house on a site, at least in my view, is where you approach the main entrance from the north and proceed through the hallway towards the reception or living rooms which, in turn, open towards the south and west.

This might leave the kitchen and utility room somewhere at the eastern or northern end of the house. Thus, the living rooms not only benefit from optimal solar gain, but also look out upon and provide access to the more private external areas.

In an approach from the south you will need to balance the ‘semi-public’ area of car parking and entry with the ‘semi-private area’ of patio / garden space, achieving some sort of discreet separation. In such a case, it’s useful to have a wider garden – perhaps positioning the main entrance and car parking towards the east and living rooms towards the west.

With a southerly garden facing the road, depth will assist in achieving separation between the semi-public and semi-private functions. Of course hedging and small trees as well as different ground materials can help to create spatial separation too.

Computer software can help to model the house in terms of orientation and energy gains. The Passive House Planning Package (PHPP) is a tool I find particularly incisive and powerful to predict the energy balance of a house although there are others including those that offer 3D modelling.

PHPP will assist in, among other things, determining the amount of energy you will need year-round and sizing your boiler accordingly, for the lowest possible running costs. It will also specify the systems required to achieve a comfortable interior, one without draughts and with a balanced temperature as well as healthy air supply throughout the building.

For the orientation, should the house be on a straight North/South axis with living areas facing south?

It’s not necessary to follow this axis, you can angle it up to 25 degrees off that line and still get a very good result in terms of solar gains. There’s quite a tolerance in the calculations as the amount and positioning of glazing will have a significant role to play.

Design packages like PHPP are comprehensive in providing information such as how far back the window reveal and head should be to achieve better solar gains. It’s a give and take between the amount of glazing and the amount of insulation you have to add to make up for the heat loss.

In new builds, a fabric first approach should be adopted, placing emphasis on building the house to be airtight and well ventilated.

Depending on the topography you may want to build the house at a certain angle to avoid the need for expensive foundations. So this could restrict your orientation but shouldn’t be a limiting factor. Very narrow sites, however, may mean having to place your living areas more northerly facing.

My own house faces north because we built on the hillside and there’s a bank on the south side. Oftentimes views can face north too, be it of a tree, stream or a mountain, and you should make the most of these with picture windows.

You’ll just have to make up for the thermal losses by adding insulation and investing in higher performing windows. The design software will help you determine how to achieve a good balance.

How about the orientation of my front and back doors?

In general, it’s good for your main entry point to be central in order to gain access to any area of the house when you come in – instead of having to walk down a long hallway, for instance. Inside it’s important to segregate the bedrooms and other private areas from the semi-public spaces. Visitors will generally be given access to one or two rooms and these should be connected.

The typical bungalow design with gable access can be problematic for these reasons.

You have to think of how the building is going to be read – in a cottage the front door is hugely important, there’s a whole narrative attached to it. You need to stay true to the rhetoric of the building.

At the other end of the spectrum you have modernist buildings – the lines are all so clean and uniform it may take you a while to find the entrance!

There’s a hugely utilitarian element to the back door, not only regarding how it connects you to the inside as seen above but also to the landscape – is it near the shed, does it provide direct access to the garden and clothes line? I’d generally have it located to the eastern end, with access to the utility room.

Can I build on top of a hill? How can I make the most of the views?

The planners will want to ensure your house blends into the landscape and generally, building on the highest point puts the house too much on show. It will also expose you more to high winds and the weather, which will affect the energy performance of the building.

When designing any building it needs to have ‘visual absorption capacities’, it should be a backdrop as opposed to a silhouette. Even in a built-up area the building needs to blend in with its peers.

On a sloping site, a split level design will be more economical to build than cut-and-fill but if the terrain is very steep, you will in all likelihood need to dig. In that case you could consider adding a story beneath the cut and fill area, or build the house so that part of it consists of a basement.

There’s a lot to dig out if you want a flat level and you also have to deal with the bank, including retaining walls and also waterproofing. When you do cut and fill you generally pick the lowest contour but it’s still a considerable dig and the costs can quickly mount if you hit rock.