The pandemic has focused self-builders’ minds on the already popular topic of going off grid, meaning no electricity, gas, water or sewerage connections. But how feasible is it to totally disconnect, asks Patrick Waterfield.

[adrotate banner=”53″]

In this article we cover:

- What off grid means, the pros and cons

- How you can go off grid for electricity

- How to set up an off grid electricity system

- How much an off grid electricity setup costs, including usage data

- Issues with loans, warranties and other hurdles

- How to adopt an off grid mindset

The prospects of freedom from utilities, a more sustainable lifestyle and overall greater independence, especially in times of economic and societal uncertainty, hold a strong appeal.

Out of necessity, many rural houses in Ireland already have no mains sewerage connection, relying on septic tanks/mini water-treatment units and percolation areas.

[adrotate banner="58"]Furthermore, enough water falls on this island to cater for our needs. Given a sufficient catchment area, storage and treatment/filtration, rainwater harvesting is a tried and tested method. On most rural sites there is also the possibility of drilling a well.

Many houses, again mostly in rural areas, have no connection to a mains gas supply with LPG and oil tanks widely available. So for this article we shall focus solely on going off grid for electricity.

How do you go off grid?

From a purely economic viewpoint, a remote location may favour an off grid approach due to the potentially high cost of providing an electricity supply where one does not already exist. We could be talking tens of thousands of pounds/euros which would buy a considerable amount of on-site generation and storage.

Technically speaking, going off grid means not only not importing mains electricity but, also, not being able to export excess generation to the grid. This will have an impact on the economics (although the price for “spilled” generation has not tended to be very favourable to date, low in NI and non-existent in ROI) and, more significantly perhaps, you will have no backup if your system fails.

A halfway step towards going off grid might therefore be providing all your electricity needs on site but still having connection to the grid. In this way you would still have the security of supply of a mains connection should you need it and would be able to spill your excess generation back to the grid.

Note that equipment would be needed to effect a smooth switchover between on-site and grid supply and that various standing charges may apply for provision of supply even if you don’t use it.

Off grid set up

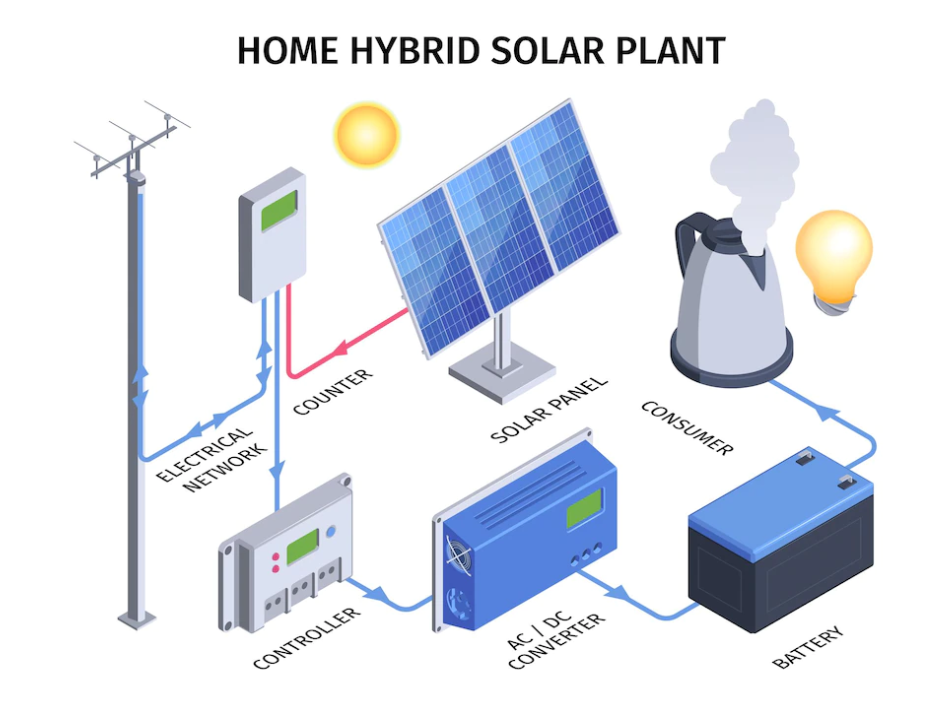

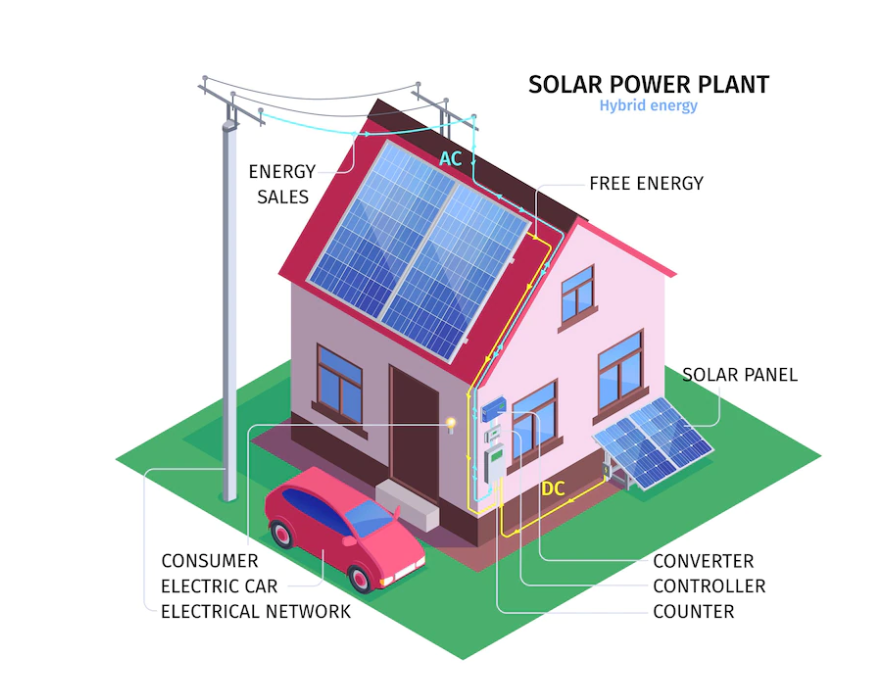

Planning regulations permitting, a combination of photovoltaic (PV) panels, wind turbine and domestic battery storage, possibly linked into electric vehicle charging, could provide all the electricity needs for a well-designed house that incorporates things like low wattage appliances.

Cost wise, £30k/€40k would be a reasonable ballpark for a 5kWp PV system with 10kWh battery capacity and 11kW LPG-fired generator, such as would serve a medium-to-large home with 5,000kWh electricity consumption per year. The notional analysis shown here assumes this level of consumption

Bear in mind that typically only about 1,250 to 1,350 kWh of solar output would be used directly, the rest would be via battery or generator (the more of one, the less of the other). You could up the size of the PV array and batteries, to roughly 10kWp and 20kWh, to reduce the load on the generator but this would raise the overall cost to about £50k/€60k.

The reason for the generator is that off grid makes the most sense in a remote location where the cost of a new grid connection could be substantial. In this context, running the generator is unlikely to annoy neighbours. The same might not be said for an urban/suburban setting, where grid connection is advantageous.

In a grid-connected system, any excess generation from the panels in summer would be exported to the grid and, in NI, you would be paid for. Though at a lower rate than for power imported, thus allowing the PV to operate at full output at all times.

The generator or grid connection is needed to avoid having to oversize the PV and batteries to cover worst case conditions, which would not only increase costs but also require powering down of the PV system (and resultant “lost” generation) in summer/good weather.

To avoid running a generator at all, though it would be prudent to have one just in case, you would need about 30kWp of panels and 90kWh battery capacity to cover all your needs, which could cost around £135k/€150k all in.

Images from macrovector at freepik.com

Hurdles

On a very basic practical level, will you be able to get a mortgage or other loan to build a new off-grid house? Most of the High Street lenders would probably pass, though those already involved with self-build loans might be more approachable.

You might find, however, that the maximum percentage of loan to end value (another thorny issue!) would be low, probably less than 50 per cent.

Planning permission is never guaranteed to be straightforward with any build and going off grid is only likely to complicate things further. Make sure you understand the rules very clearly and consult with the planning authority at an early stage – be open and clear about your proposals. Consult with neighbours too to make sure they are on your side.

Also, it may be more difficult to get insurance for an off-grid property.

What we can all do

Installing a small amount of renewables, e.g. solar thermal or PV panels, is a good option for most of us, especially if there are grants available as is the case for most existing homes in ROI.

Beyond that, we are all guilty of using energy, and water, when we don’t really need to. Flicking a switch or turning a tap is just too easy! Cutting your shower time by just one minute can not only reduce water consumption but also up to £120/€135 per year on energy costs for a family of four.

Decoupling from wifi might be a step too far for many of us, especially those who work from home or have teenage kids. However, increasingly these days, holiday companies are promoting off grid properties as a way of taking a break from the trappings of everyday modern life.

Interestingly, there is already a growing body of off-gridders in the UK, some 75,000 people, who are saving up to 90 per cent of their energy and water usage, and spending less than half in utility bills than the average family home.

Statistics aren’t available for Ireland but all in all, even if the full off grid dream is cost prohibitive here, adopting elements of an off grid mindset, even permaculture, can no doubt help us de-stress and minimise our impact on the environment.