Love them or hate them, Irish bungalows are now part of vernacular architecture, representing the first modern mass self-build movement.

In this article Marion McGarry covers:

- How bungalow design has evolved since the 1970s

- How bungalows met rural Ireland’s need for affordable housing

- Overview of Jack Fitzsimons’ seminal book Bungalow Bliss

- Bungalows as a blight on the landscape in the 1980s and 1990s

- How bungalows cemented their place in vernacular architecture

- Book review of Bungalow Bliss Bias (published 2019), a book by Jack’s son Kennas

“To anybody about to build a home this book can be confidently recommended” so wrote one commentator on Bungalow Bliss, first published in 1971, which went on to profoundly influence Irish self-builders and subsequently marking the surrounding countryside.

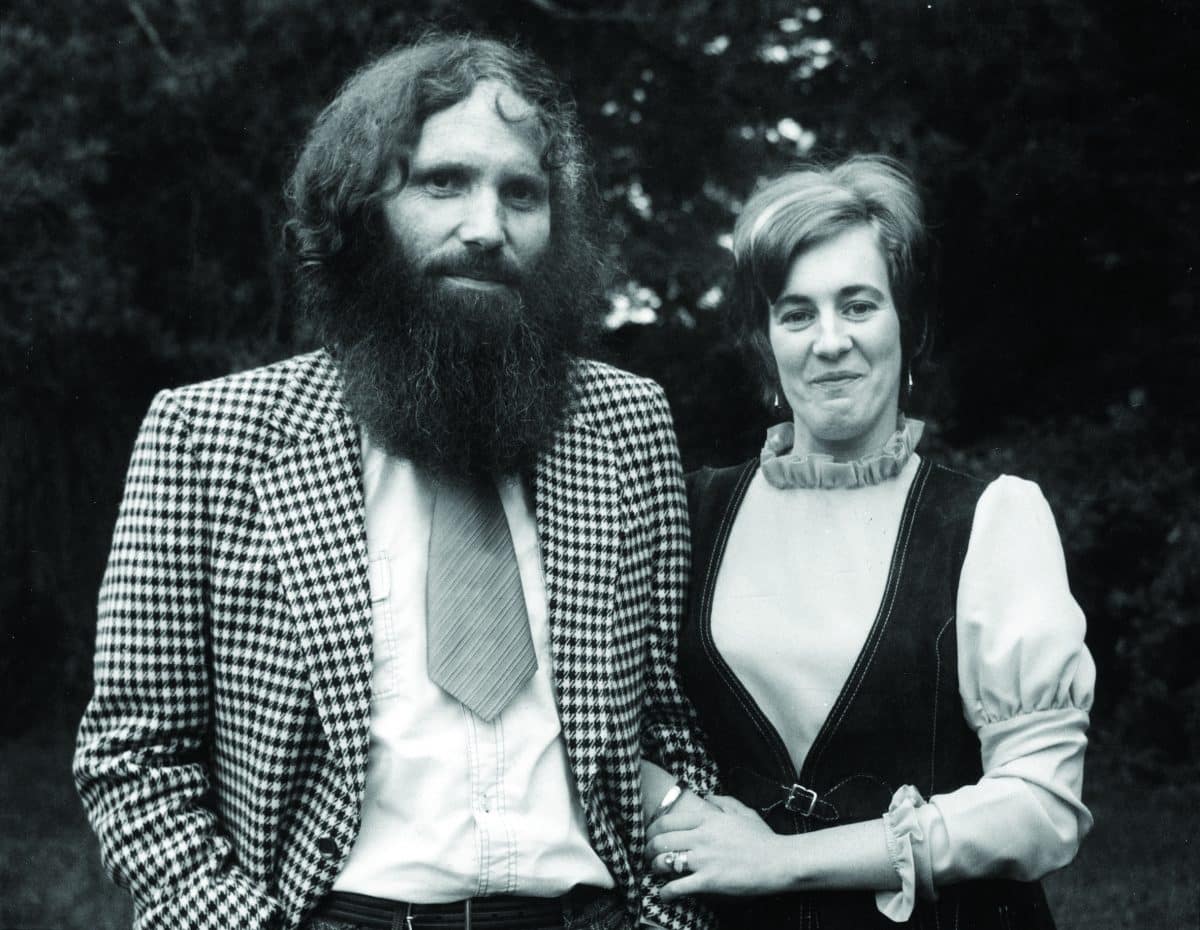

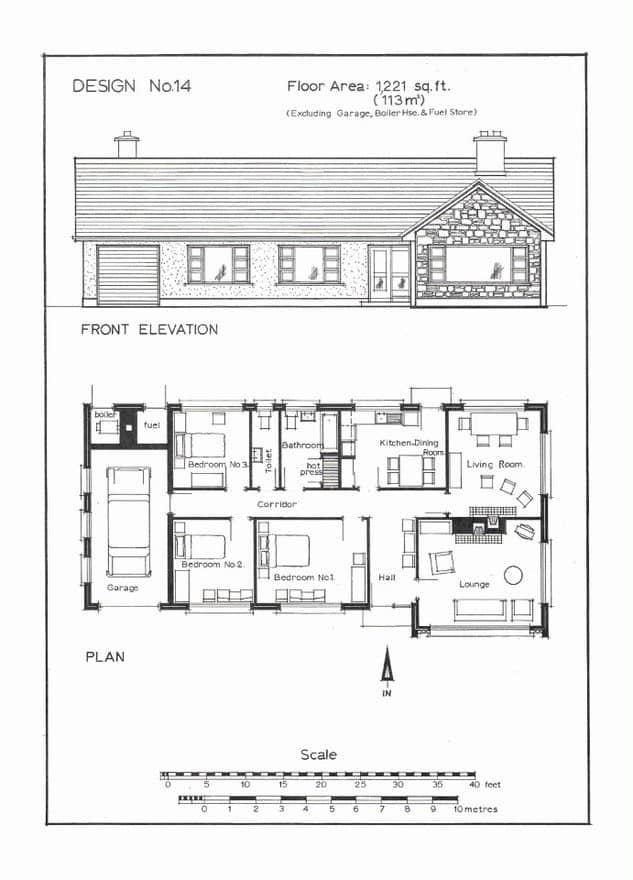

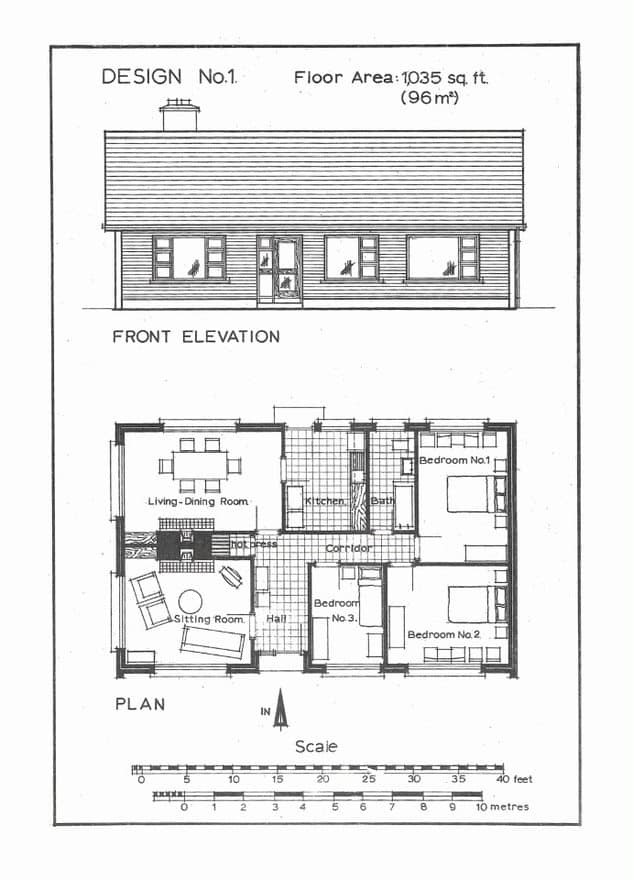

It was a modern pattern book containing 20 comprehensible and affordable plans for bungalows self published by the late Jack Fitzsimons, an architect from Meath. Since the first edition in 1971, 12 followed alongside over twenty reprints until the year 2000. It was one of many Irish self-build manuals and undoubtedly the most successful.

Books like Bungalow Bliss democratised the self-building process by removing architects and allowing clients and their builder-contractors to have more say.

Yet Irish bungalows and rural one-off housing from the period were subject to scathing criticism for their lack of planning, social, environmental and aesthetic considerations.

Bungalow Bliss

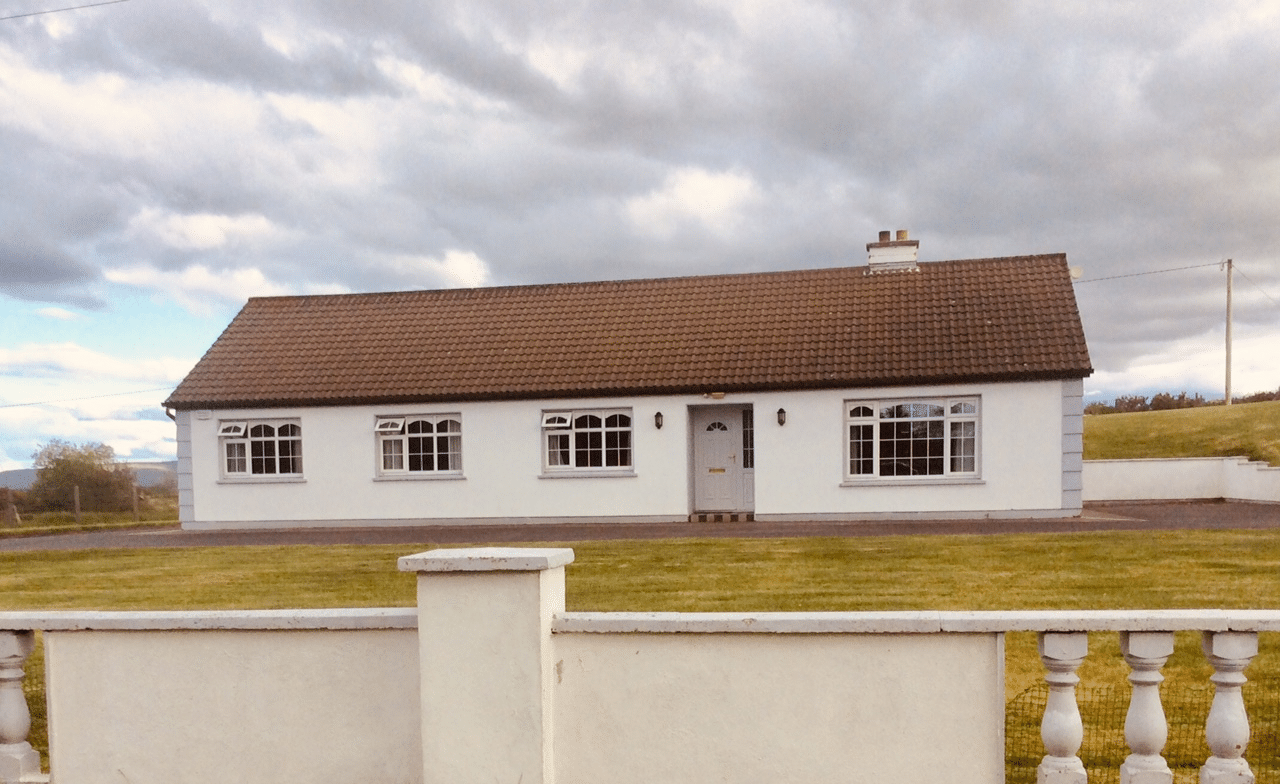

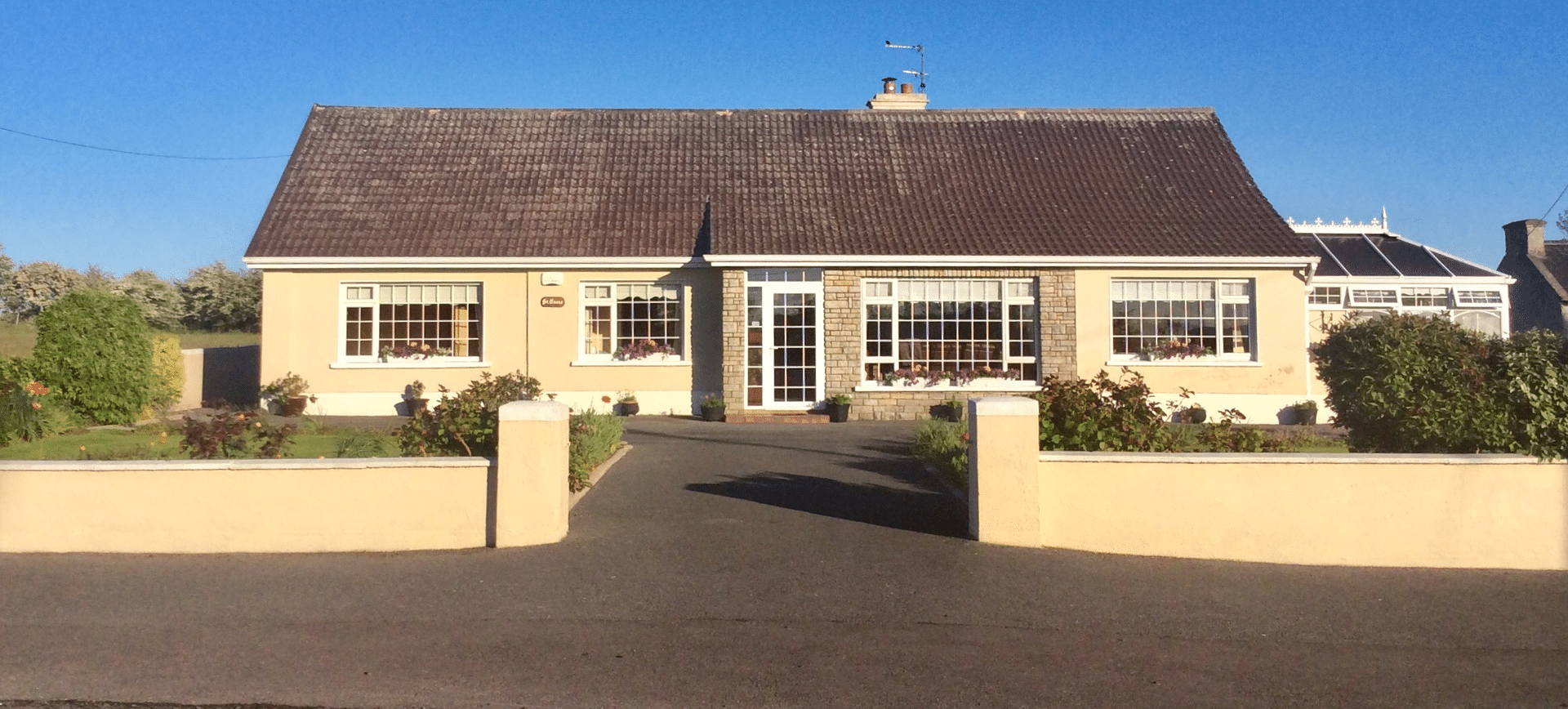

The house typified in Bungalow Bliss was usually rural, one-off, one-storey, concrete, with three to four bedrooms surrounded by a tarmac driveway and lawn. New, twentieth-century notions of individuality led to the inclusions of such fancies as arches, balustrades and stone cladding (which rarely matched the surrounding stone in the landscape).

Modern bungalows were not tucked away up a lane or in a copse of trees, but were loud, proud and very visible. Many of the occupants were from a farming background but the first of their generation not to work the land. They relied on cars to get to their blue- or white-collar jobs elsewhere. The bungalow brought a modern home within financial reach for many families.

A typical layout included a central corridor off which the rooms were entered, with separate living rooms, bedrooms and, crucially, an indoor toilet and bathroom. Bungalows had fireplaces with ‘boilers’ attached, that could heat water and also distribute heat via radiators placed throughout the house. Bungalows notably included a defined sitting room, the descendent of the parlour or good room.

Many pointed out that the bungalows represented Ireland’s gradual escape from poverty. The ability to build one’s own home also signified a reaction against an unfair inheritance system: in the past, the family house was passed on intact to the eldest son, whose siblings then had to find homes.

Often, they emigrated or migrated to towns, or moved into public housing. When Bungalow Bliss was published it delivered house plans to this audience at a modest cost. Others were delighted at the modern and exciting looking templates it offered. However, as such bungalows were viewed as not guided by the edified hand of the architect they were often derided as being tasteless or tacky.

Bungalow blight

The 1970s-1990s-era bungalow is seen in all parts of the countryside in Ireland, evidence of the increasingly expanding middle class of that time. Throughout the 1980s, bungalows became increasingly noticeable, dotting the Irish countryside as sharp white rectangles standing out from beautiful rural areas.

Often their whiteness was compared to Southfork, the iconic mansion from the most popular TV show of the era, Dallas. Many thus became known as Dallas bungalows, or Spanish bungalows due to the fancy Mediterranean features such as hacienda style arches, balustrades or Doric columns. People who built such bungalows were sometimes seen to have the terrible Irish sin of ‘notions’.

These mixtures of classical and exotic elements fed the rage of commentators who decried the fact that bungalows looked nothing like traditional Irish architecture. Planning laws meant it was easier to build near an old ruined cottage, which made the contrast between these bungalows and their predecessors even starker.

The bungalow, it was said, was a blot on the Irish landscape and evident of poor planning laws. Some called for aesthetics to be regulated in Irish planning laws. This in some ways is now the case in England with Paragraph 79 (formerly Paragraph 55) of the National Planning Policy Framework which aims to curb people from building new isolated homes in the open countryside, and allows for one-off housing in the countryside if the design is “of exceptional quality”.

Bungalows certainly did not have the beauty, uniformity or ability to blend harmoniously into the countryside that the thatched Irish cottage had. Yet the cottage had provided an early inspiration to Fitzsimons to publish Bungalow Bliss: it was the poor living conditions within them that became essentially his clarion call to improve standards of dwelling in rural Ireland.

Bungalow bias

A new book called Bungalow Bliss Bias, has been published posthumously by Jack’s son Kennas Fitzsimons (Jack died in 2014). It acknowledges the importance of the original book Bungalow Bliss and aims to provide historical context for it.

In Bias, Jack Fitzsimons defends the designs of Bungalow Bliss and answers his many detractors (who included at one point, Dermot Bannon but more famously journalist Frank McDonald), standing his ground by emphasising the necessity of his book at a time when few houses were being built and when the “architect belonged to an extinct or foreign species”.

He maintains he filled a gap at a time of need providing what he described as a lay-man’s building bible. Yet in doing so he became, according to one critic, a “herobuilder to the lower middle classes”.

Fitzsimons also provides a fascinating and candid insight into how his own impoverished childhood influenced his work and informed the original book. Speaking from experience he notes that living standards in old Irish cottages were ‘wretched’; he remembers the grim minutiae of a mud walled, thatched, damp dwelling with poor light sources, inadequate heating, poor insulation and a total lack of plumbing.

Later he saw similar living conditions when working for Meath County Council before qualifying as an architect and moving into private practice. Bungalow Bliss, a self-published book, was a reaction to these impoverished and unhealthy living conditions.

It also met what Fitzsimons saw as a demand for rural builds in a country where “architects were not generally available to help people with housing problems in rural areas”. At that time grants meant that housebuilding was encouraged and made more possible than today, but the problem was the lack of designs.

Fitzsimons’ book gave advice on planning and septic tanks, and espoused high standards in the plans: for example, external walls were of the cavity type when most new houses had inferior hollow block walls. However, he said he deliberately did not include details that might be a problem for ‘do-it-yourself builders’.