It’s possible to build your house with oak – find out how you can do it, the different configurations, cost, benefits and drawbacks.

In this article we cover:

- What is an oak build

- How much does it cost and how does it compare with a traditional build?

- Different post and beam structures from cruck to box frames

- How to use oak in your build: entire structure vs roof only

- How to specify the right type for your build

- Green versus seasoned

- Thermal performance, fire and pest resistance

In many countries and cultures, oak remains a symbol of strength and survival. In construction, green oak is especially regarded as being environmentally friendly as well as renowned for its beauty, durability, strength and longevity.

When we refer to the use of oak as a material for building houses and extensions, we’re talking about structural timber.

These building are ‘timber framed’ but not ‘timber frame’. Timber frame is a term that refers to light-weight prefabricated timber panels. A surprisingly large number of oak building companies exist across the UK and Ireland, but a relatively small percentage of these specialise in building houses, the remainder providing anything from orangeries and conservatories to stables, barns and garages.

Oak structures

All oak buildings start with a structural frame or skeleton, which can be filled, encased or left exposed according to the design objectives. Traditionally, the infill panels were of wattle and daub, clay or stone and later, of brick. Nowadays they are more likely to be of insulation material.

The three principal traditional types of frame consisted of cruck, box and aisled frames. Nowadays, these styles are often merged and adapted to form more complex frames.

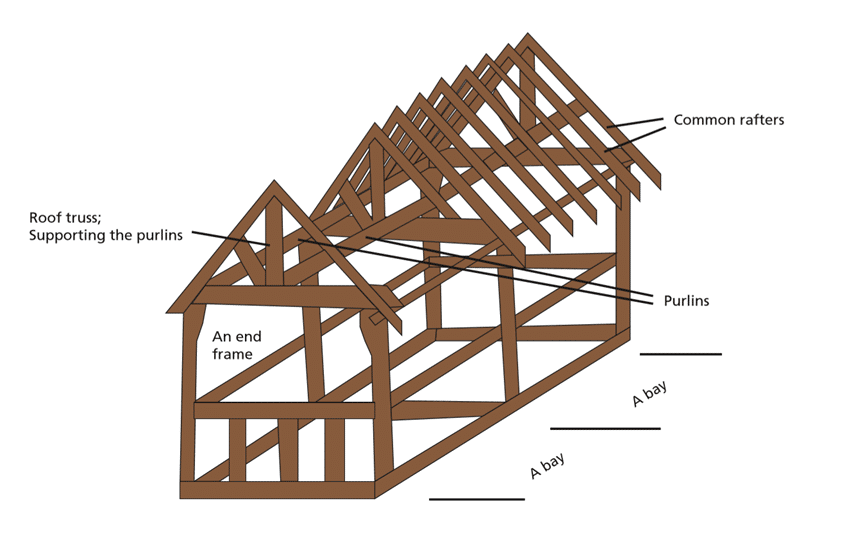

The basic principle of them all is the ‘post and beam’ structure which consists of two or more uprights supporting a horizontal beam. Each set of posts and beams are then repeated in bays along the length of the building. As these frames carry the roof, open plan spaces are easy to create within the building.

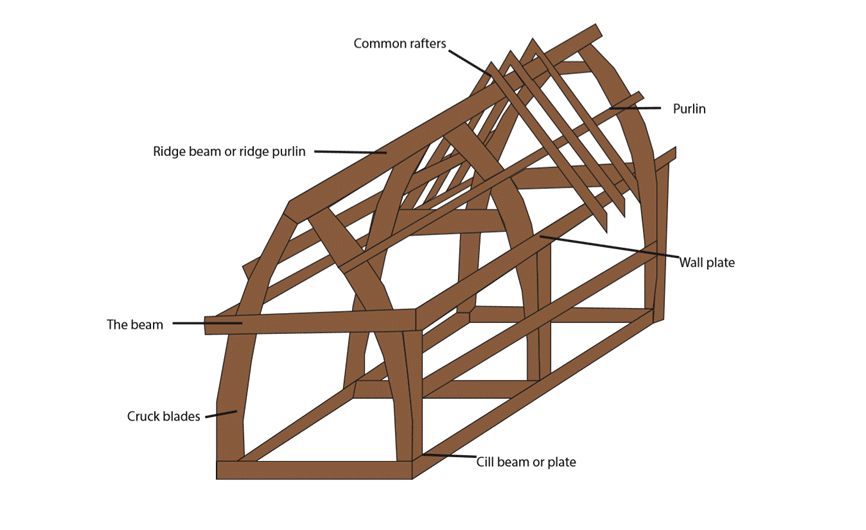

Cruck frames were the earliest and are still in use today. The principal structural members are taken in pairs from a single trunk, usually but not always, curved; so that each member is mirrored on each side of a large ‘A’ shaped frame. The two main supports are set narrow end up and fixed at the top whilst a beam is usually carried across them about halfway up, to support the main first floor. Old cruck houses can still be seen with the frame structure exposed on the external gables.

The box frame became more common as large trees became scarce during the latter part of the Middle Ages, so shorter timbers had to be used. The frame is created using larger members to form the skeleton of the box, with lighter pieces infilling the spaces between. The ‘boxes’ can be set side by side and on top of each other to form more varied shapes and sizes of building. Tudor period houses with vertical timbers and whitewashed infill panels were usually built using this type of structure.

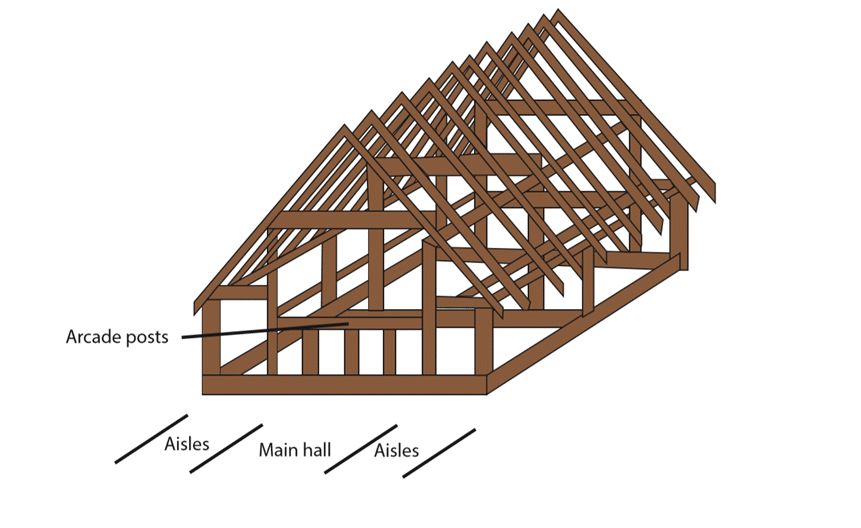

Larger than cruck houses, ‘Hall Houses’ or aisle frames consisted of frames which were formed using a set of columned frames at usually 16’ (4.88m) intervals to create bays. The rafters were extended down past the main frame onto external walls outside the main frames.

Truss frames are constructed using roof trusses carried on vertical posts or columns. The truss is made up of a web of triangles of varying complexity (many interesting examples can be seen in our churches), to give the roof lateral rigidity and to prevent the support posts from spreading. This is probably the most common form of frame in use today.

How to use oak in your build

Roof, wall and floor sub-frames can be prepared off site and assembled as a complete oak frame on site, which makes it a modern method of construction.

During the design phase, careful consideration will have been given to the condition of the oak to be used and its estimated shrinkage rate, so it is preferable to source it at a very early stage. A green oak-framed building should not be rapidly dried after construction as this can cause unduly dramatic splits in the wood.

If glazing is to be applied to the face of the frame, then the differential movement due to shrinkage needs to be taken into account and the usual solution is to use oak cover boards over the joints.

When extending a masonry or timber frame home with an oak framed structure, then expansion or contraction joints need to be used where differential movement would cause problems.

Junctions between walls, roofs, foundations and glazing all need to be properly detailed.

The traditional method of jointing green oak frames is by mortise and tenon joints. Oak pegs are driven into holes through the joints and the ends of the pegs are sawn off to give a neat finish after the wood has dried in the building and the pegs have been re-tightened.

To get started, find a designer with detailed knowledge of these structures, or alternatively, many of the oak building companies will work with your designer. Then get a preliminary design prepared to check estimated costs.

If you intend to leave parts of the frame exposed externally, before you submit a planning application, consult the planners to find out what they are likely to think of it.

Building control will require structural calculations to prove that the structure complies with the relevant standards. If the oak frame building company do not provide these, you will need to engage a structural engineer, which is the smart thing to do at the design stage of any building project.

Find out all you can about the type of timber which is going to be used.

- Is it sustainably sourced?

- What is the age and moisture content?

- Has it been properly strength graded?

- How do you want it to look (i.e. traditional or modern) and where will it be exposed?

Specification

In Europe there are 22 species of oak, but in the UK and Ireland we most commonly use the two most northerly-growing species, i.e. pedunculate or common oak (Quercus robur) and sessile oak (Quercus petraea). The evergreen holm oak (Quercus ilex) and the cork oak (Quercus suber) can also be obtained.

When buying oak or oak frames, or in fact any timber, care should be taken to ensure that it is certified from organisations which promote sustainable forest management such as the FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) or PEFC (Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification).

Sawn oak in the UK and Ireland is usually limited to maximum sizes of about 9.500m long and 500 x 500mm section size, but some European forests can provide longer members if required. Commonly used section sizes range from 150 x 150mm to 250 x 250mm, in 50mm increments.

Green vs Seasoned

Oak for structural use is normally supplied in two main forms; green and seasoned. The main advantages of using green is that frames will dry, shrink and tighten as the building dries. It is also much easier to work for shaping and making joints, etc.

Green oak has simply been recently sawn (it’s best described as being wet) whilst seasoned oak has been allowed to dry naturally, usually sheltered but ventilated, in the open air. Seasoning can take anything between three to ten years depending on the thickness of the wood. When buying ‘dry’ oak for parts of the structure where movement is undesirable, it is important to find out how old and dry it is and also to try to anticipate the conditions in use.

In decreasing order of dryness and of cost, oak is typically available as:

- Kiln dried (approximate moisture of 15 per cent)

- Air dried (approximate moisture of 20-30 per cent)

- Partly seasoned (approximate moisture of 20-60 per cent)

- Fresh cut from trees felled within 18-36 months (approximate moisture of 60-80 per cent)

Any oak used for structural purposes should be strength graded in accordance with BS5756 to ensure that it is capable of taking the intended loads. The shear strength of wood is around 10-15 per cent of its tensile strength in the direction of the grain and because shear strength is weakened by knots and associated faults such as through-grain cracks, most of the criteria related to sorting for strength and quality is related to knots.

As with all wood, the strength of oak is fundamentally affected by the direction of the load in relation to the grain. Natural seasoning does not weaken properly designed oak frames, but makes the timber harder and stronger. The grading process also limits the angle of grain direction and since cracks and splits generally run parallel to the grain, these do not weaken the timber. Moisture content affects density, which in turn affects bending strength, so these factors must be known in order to predict load-bearing ability.

Forest rotation cycles can be 200 years or more, as an oak tree can take up to 150 years before it is ready for use as structural timber, although in practice, much of it is felled at an age of between 90 to 120 years old.

Even though most of the oak used for construction is green, it is occasionally necessary to use a dry beam, for example for joists, where it is preferable that shrinkage and movement is minimised. Dry oak is not customarily used for whole structures due to availability and cost and the fact that green oak will eventually dry inside the building to achieve a similar moisture content anyway. Also, green oak is easier to cut and shape than dry oak.

Seasoned oak will have weathered, split, moved out of square and opened around knots. This all gives it character, but the builder may require it to be recut to replace existing elements exactly during restoration or to ensure uniformity where it is necessary. Kiln drying can reduce the moisture content much faster, but the timber can suffer from discolouration throughout the section.

Many types of wood, not just oak, contain acetic acid which can cause corrosion in metals at concentrations as low as 0.5 ppm in air. Kiln-dried wood is more likely to cause corrosion when in contact with ferrous metals than air-dried wood. Mostly though, kiln-dried or airdried oak is usually reserved for furniture, decorative joinery, floorboards or fireplace surrounds, etc.

Quercitannic acid (more commonly known as tannic acid) is present in all forms of oak timber, but is fixed in the dry, aged wood. With higher moisture contents found in wet oak or oak that is exposed to the weather, the acid can leach and leave brown stains on the wood. Over time, green oak will weather to a silvery grey. These characteristics add to the charm of the material.

For those who wish to retain the colour of green oak there are various treatments and wax oils on the market. Just keep in mind that if used externally, most of these will need to be re-applied annually. Indoors, it is useful to oil the timber in rooms with high humidity or where water can be splashed around. Dried oak timber products can be treated pretty much as you would finish any other hardwood.

All oak frames will need to be cleaned once the construction phase is over. Some self-builders will take on this task themselves to save on costs, but be warned, it is labour intensive. Oxalic acid is the recommended weapon of choice for tackling timber staining, but do take care to use it safely and adhere to the health and safety guidance relevant to the product. Sandblasting is another technique which is used, but it can be messy. Of course, it is always good practice to keep exposed timber covered during construction to reduce cleaning effort later.

Thermal performance, fire and pest resistance

Unfortunately, dense wood is not a very good insulator. Dry oak has a thermal conductivity of about the same as a standard lightweight aerated concrete block and increasing the moisture content increases the thermal conductivity, so the old look of exposed external timbers is nowadays harder to achieve.

Some oak frame companies have managed to build walls with exposed external timbers which have reasonable U-values but airtightness obviously becomes an issue when green oak shrinks. If external exposed timber is not a priority, then it is easier to simply encapsulate the oak frame with an unbroken, airtight, insulated and weather-proof envelope. For example, SIPs (Structural Insulated Panels) can be used in order to achieve PassivHaus standards, but other solutions such as more traditional insulated cavity walls, if properly designed and built, will work just as well.

Oak is a relatively dense hardwood which performs well under fire due to the effects of charring (i.e. carbonisation), where timber beneath the charred layer does not lose significant strength because the thermal conductivity is lower and fire penetration is slowed down. It is the structural engineer’s responsibility to determine the timber sizes using the estimated ‘residual’ section size to maintain its load-bearing capability after fire has occurred.

Pests of interest to builders and homeowners include wood-boring weevils, the powder post beetle and the common furniture beetle. The death watch beetle is more common in the south of Ireland than in northern regions. The good news is that these can be controlled by keeping the wood dry and properly ventilated, as timber which is maintained in dry condition is at lower risk of insect attack.

Cost

An oak-framed dwelling or extension need not be inordinately costly. Typically, for raw timber freshly sawn green oak will cost around £1,000/€1,200 per cubic metre (plus VAT). This equates to £100/€120 for a five metre long beam with a section of 100mm x 200mm. Air-dried oak will cost about 20 per cent more, depending on age and quality. Finished timber (planed and oiled) will cost more.

Commonly used methods for limiting costs include just making the primary members (i.e. the structural frame) from oak and the secondary members such as rafters and joists from cheaper timber.

Also consider just giving the main rooms the oak treatment. Many selfbuilders use oak only for features such as roof trusses, lintels and ceiling beams within a block built or timber frame house. The oak theme can be carried through a house by using oak floorboards, skirting boards, architraves and mantles, etc