You guide to creating a build schedule, what information it should contain and when to change it.

In this article we cover:

- What is a build schedule

- A typical day in the life of a project manager

- Top 3 project management tips

- Creating a Gantt Chart

- Inputting data

- Information your construction schedule should contain

- Snag lists

- Making sure the schedule works

- When to change the programme

- Typical things that can go wrong and how to troubleshoot

The first articles in this series led up to this point of actually producing the programme. Here are the elements included in a construction programme or build schedule.

Gantt Chart

Unless you actually prefer the old ‘rip it up and start again’ method of creating handwritten paper programmes, if you do a little research on how to create a construction programme, you will almost certainly arrive at the conclusion that the Gantt Chart is the tool of choice. There are other solutions available so take time to check them out too. For now, we will assume that you agree with the vast majority of the building industry and have obtained an easy to use Gantt software solution.

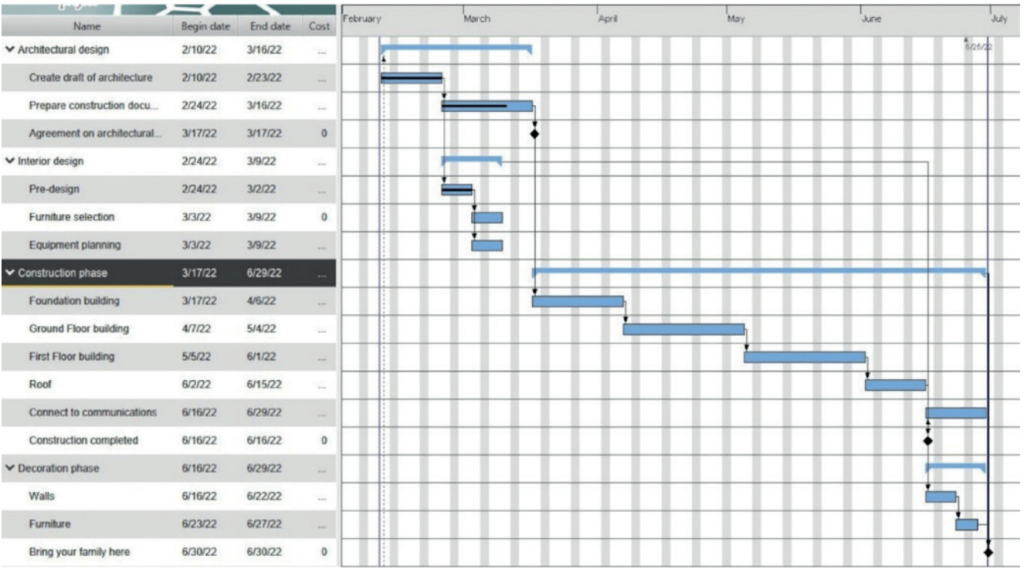

So what exactly is a Gantt chart? The original Gantt chart idea was developed over 100 years ago by Henry L Gantt and a colleague Frederick Taylor. It was a type of horizontal bar graph that shows activities on the vertical axis and time expressed along the horizontal axis. Similar charts are still produced today on spreadsheets or tables, for simple projects.

[adrotate banner="58"]The main disadvantage of such charts is that changing them tends to be a laborious task, so it is all too easy to let them run out of date. An out of date construction programme is virtually useless, so it makes much better sense to exploit the potential of today’s information technology.

A suitable construction programme software solution will show you, on a Gantt chart, the activities that your teams will work on, how long it will take to do each one and the start and finish times. Importantly, it shows when and where some activities will depend on others and which tasks will need other tasks to be completed before they can start.

It gives you a simple graphical way of viewing and managing your project and provides a very easy process of moving and adjusting task timelines. Furthermore, it allows you to easily manage the financial aspects and to quickly envisage ‘Plan B’ scenarios should the need arise.

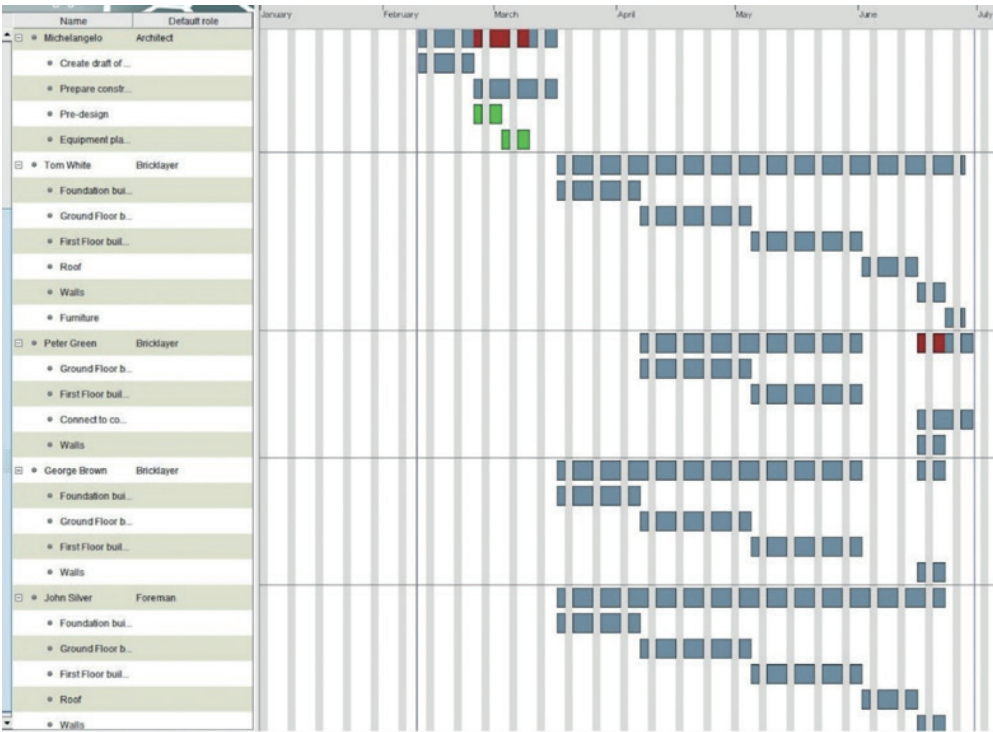

More advanced programme software will do much more than merely allow you to produce Gantt charts. In these, the primary Gantt chart will produce, usually on another tab, Key Resources charts which allow you to rapidly identify when each individual or team will be involved, what they are responsible for and when they will need to achieve their targets. It should let you plan and manipulate financial and materials resources and to set project milestones and benchmarks.

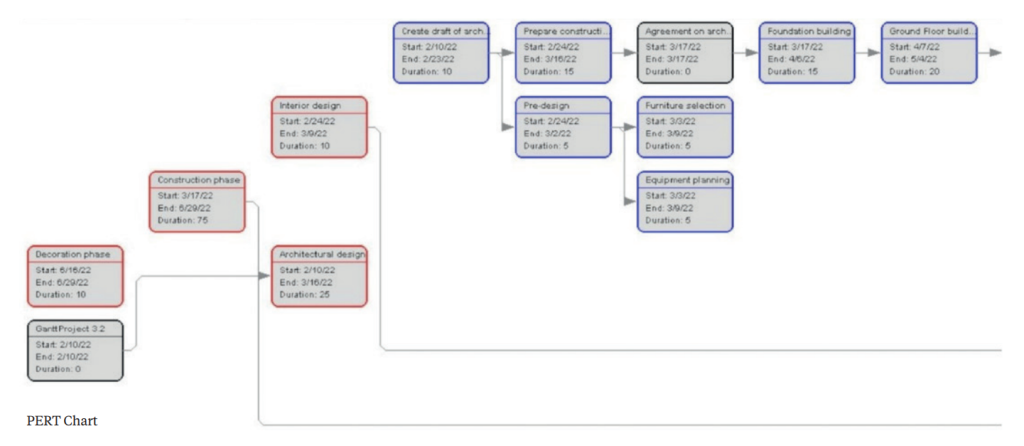

The primary chart should also produce a PERT chart. PERT is an acronym for Project (or Programme)

Evaluation and Review Technique. This is a free version of the Gantt chart and it maps out a diagram, similar to a flow chart, of activities or tasks and timelines and gives a visual illustration of interdependent and autonomous tasks, with arrows showing the direction or flow of work.

Your software should ideally highlight critical path information automatically, showing the string of critical activities that will take the longest time to complete. The duration of this critical path string will be the minimum time required for completing the whole project, so any delays in critical activities will extend the total time needed for project completion.

Inputting data

Usually, you would begin entering data by using task names or activities (written in the left hand column) and then horizontal time bars which represent the duration of the tasks, corresponding to points in time along the top row of the chart. Time may be shown in days, weeks or months, depending on the level of detail that you need. Most domestic building projects can be shown on a weekly timescale, with the facility to break each week down into days or half days where necessary.

Principal activities, such as for example the substructure, preparatory site works or the roofing may be further broken down into those elements which are to be subcontracted to different teams. Certain preliminaries will need a separate bar for setting up, operation and dismantling. Others such as the use of power and other services may occupy a constant price bar through much of the project. Long time bars, say those lasting longer than four weeks, should be split to reflect logical stages of work which contribute to the overall activity, so that interim payments can be allocated more precisely.

You will need to learn and practice how to use whichever software package you have opted for, so get started as early as possible. Create a small imaginary project just to rehearse how it all should work and how you could make improvements. It can be more useful to everyone if you create a chart that covers a project at the macro level, with subcharts for individual teams or activities. The most useful skills to learn will be how to optimise the activity time bars in relation to each other, to make sure that there are no unplanned breaks in linked tasks and how to find opportunities to run tasks concurrently when they do not need to depend on each other.

The aim of the chart is to try and make things clear and concise for all of the people involved. Too much complexity leads to information overload, so you should avoid overwhelming your teams with information that they don’t need. It is all too easy to get bogged down in too much detail, such as trying to micromanage activities which could be better left to the subcontractors or team leaders to manage themselves.

Usually, team leaders will have their own systems for briefing their teams, setting up work and closing down and clearing up after their phase is complete. The leaders may also be able to attend meetings and be available for inspections whilst their teams carry on with work in hand. Apart from the pre-construction planning meetings then all the other ‘non productive’ time should be included in each team’s total activity time bars.

Do take the opportunity which the software offers, of simulating different scenarios to try to find the most advantageous solution to phasing the work so that it flows as smoothly as possible throughout the timelines of the project. If you have the time, it can be very useful to rehearse ‘what if’ scenarios to see how your programme could be adapted to deal with unexpected events if need be. Information the schedule should contain You will of course, want to ensure that critical tasks are given to those who have the knowledge and skills to complete them correctly and on time, so you have to know each team’s strengths and weaknesses. Allocating key resources (human, material and financial) can be shown under various tabs on the Gantt chart software. I would suggest that your programme should aim to show the following key information:

- Public holidays, builders’ holidays and weekends. Block these dates out.

- Other breaks which you and any of the design or construction teams will need.

- Preliminaries.

- Realistic time required for each trade activity or phase of work.

- Temporary works.

- Time set aside for curing concrete and blockwork, drying out after wet trades, etc.

- Overlaps between the design and construction phases.

- Which activities depend when and where, on others.

- Sequential and simultaneous activities and standalone tasks.

- Critical paths and critical activities.

- Set milestones where each significant part of the work is to be completed.

- Set benchmarks to help ensure quality control.

- Human resources for each activity – who is doing what, where and when.

- Materials resources for each activity – what is required and when, including lead times.

- Plant, equipment and machinery resources required at any given time.

- Financial resources allocated to each activity or phase and the total cost.

- Risk identification, contingency planning and potential overruns.

- Run out dates on insurances.

- Inspection and certification points.

- Snagging, testing, commissioning and certifying periods.

- The postconstruction phase.

Note that some teams will require multiple time bars. People such as joiners, electricians and plumbers will need to be on site to get their work started (i.e. so called ‘first fix’ activities) and then come back later in the project to carry out follow up stages (i.e. ‘second fix’). Some of the specialist trades will require additional time near the end of the project to test, commission and certify their work.

If equipment has to be hired for any of the teams, find out which other teams will need it too. Try to arrange it so that hired equipment is not left sitting doing nothing for extended periods.

In addition to the routine scheduled inspections, you might also want to run independent tests such as a thermal imaging survey after the heating is up and running. This type of survey is invaluable in identifying any cold spots in the building’s thermal envelope. Remediation work on concealed or hard to reach insulation may require the builder, insulation installer, plasterer or joiner to return to fix any problems.

A day in the life of a project manager

During busy periods, make this part of each day and you will find that it takes less time as the project progresses. Each morning, as early as possible:

1. Open your construction programme software. Then review, review, review!

2. Review the previous day including photographs, notes, messages, emails, etc.

3. Review the current phase or phases of work.

4. Check what’s coming up next.

5. Check for any recent amendments to the contract documentation.

6. Check the latest weather forecast.

7. Communicate with all team leaders on site or due to arrive on site and update them as required.

8. Analyse resources. Check that everyone has got what they need or will get it on time.

9. Check the finances. Who owes what and when, to whom.

10. Get out on site and talk to the team leaders to check whether there is any new information which needs to be actioned.

11. Execute any outstanding actions, amend the programme and reissue it as required.

Snag lists

Towards the end, confirm with each team and with the certifier whether they are satisfied that the work is complete under the terms of the contract. Then book a final inspection with Building Control (NI) and get their snag list as soon as you can. This list, in conjunction with the certifier’s snag list (which may be different) will help to let you know if anyone needs to come back on site. The designer appointed to inspect and certify the work will need a copy of the Building Control final certificate (NI only) before they can issue theirs.

They will also check issues that are not directly connected to the building regulations, such as planning approval conditions and other items such as the position of the package wastewater treatment plant and subsurface irrigation system in relation to the discharge consent. There will be an extensive list of checks before full completion can be certified. Check the contract terms to see whether any single subcontractor should be released from their contract before all of them have reached the practical completion stage.

Making sure the schedule works

First of all, set up your own administration team, which should consist of yourself, your lead designer and the Quantity Surveyor (QS). You may bring in more people, but too many can lead to broken lines of communication and errors.

Most self-builders will want to involve their partners and families and this usually works best when one family member acts as the sole representative of the others. This representative should be the one in the family with the most knowledge and experience of building projects. He or she then takes on the roles of employer, project manager and principal contractor.

Administration team meetings will be in addition to the main meetings with the other teams. Your knowledge of building may be extensive enough to allow you to identify parts of the design and specifications which are missing or are not what you want, but if not then get the designer to prepare schedules of work.

Poorly prepared contract documents make for a poor experience for everyone involved. The fault may lie partly with the designer, the contractors, the suppliers or with the clients or it may be a combination of any or all of them. Ultimately, who is to blame doesn’t really matter in the grand scheme of things, but barring ‘events beyond human control’, most failures in hitting your targets will almost certainly be due to poor communication.

After you draw up the first draft of the programme, set up the first preconstruction planning meeting to get all the construction team members to review it and to request changes if they see any problems with it. At this meeting, make sure that everyone knows to whom and when they will be expected to report during any part of the works. Certain actions will require careful monitoring and control and these are generally to be found in the Health & Safety (H&S) Plan.

For instance, if a site operative temporarily removes an element of health and safety equipment to get access to something or when teams need to be informed of occurrences when the various services are to be switched on or off, etc. Teams will be familiar with keeping each other informed as they go along, but you have overall responsibility to ensure that these lines of communication actually work.

Routine meetings for the design and construction team leaders should be set up. For example if they all know that there will definitely be a progress meeting every second Wednesday at 9:00 am at the designers’ office, then no one needs to stay alert to the possibility of a late email the night before.

Depending on the intensity level of the timelines on your programme, meetings may be more or less frequent, but setting them up early in a project is a really useful way of keeping the workflow running as smoothly as possible. From personal experience, online video meetings serve a useful purpose at certain times, but cannot replace face to face meetings where a number of complex documents are being discussed.

Whilst saying that, make full use of technology to attend to rapid changes whenever you can. It can be very convenient to update the online project folder from the design office with an amended drawing and then get the relevant team leader or site foreman to call that up on their handheld device for discussion during working hours.

When the working programme has been produced and checked, issue it to everyone who needs it. You may choose to retain a master copy containing information such as costs or personal information that you wish to keep confidential. What you choose to release is up to you, but striking a careful balance between neither too much nor too little is usually best. A second preconstruction meeting may be required to address any queries that have cropped up in the intervening period.

Project Management: Top Tips

Pay everyone on time. A simple approach to interim payments would be to divide the time worked so far by the total time allocation for that activity on the programme to arrive at a fraction of the price to be paid at any given time. Assuming that work has not been held up, that the full team has been present on site and that variations have not crept in, this is an easy way to allocate the payments fairly over the time worked.

Respond to requests for information (RFIs) in good time. Contractors may need a detail of a particular part of the build to show them exactly what is required. Suppliers may need a drawing that was not included with the tender documents, such as a ceiling plan. Not only must the design team be able to respond to RFIs in a timely fashion, but the people requesting it must be able to ask soon enough so that they receive the information before it holds up work.

Allow for lead times. Finally, builders and subcontractors are human like the rest of us, so do not assume that they will necessarily remember to check that their supplies and equipment are on site before their commencement date, or indeed whether preparatory work has been done for them by others. You have taken responsibility for managing those factors, so must develop a system in your own programme for taking action in good time. If the programme software allows, set up a ‘pre delivery’ alarm system that informs you and the teams before supplies are required on site and before that, an ‘order’ alarm system to allow for any lead times required for materials, products and equipment.

When to change the programme

Review the programme regularly. Once a week may suffice but depending on what stage the building is at and how many people are on site, you might have to do this on a daily basis. Finishing out tends to be a much busier time, with more operatives on site than at the earlier stages, so you could find that you have to juggle everything more frequently to keep up a consistent flow of work.

Keep checking that your supplies and equipment will be arriving on site when you need them. Any changes to this will affect your programme. Try your best to get realistic delivery dates.

You may find that if delays arise in one area, more readily available resources can be redirected to another in order to avoid gaps in site attendance. To put it plainly, if a contractor sees the possibility of downtime due to unplanned supply gaps, their first thought is usually to head off to work on another project that they might be involved in.

It is their business and they cannot be faulted for doing so, but you should know that this situation almost always results in a struggle to get those contractors back when you want them. The key therefore is to keep the work flowing by all reasonable means possible.

You might sometimes find that a gap appearing in one activity could be taken up by another. Most important of all perhaps, is that whenever you change anything, let everyone know what is happening as soon as possible and make sure that they acknowledge.

Once contractors are appointed, contract time constraints will usually just allow you a short period of time to review the activity schedules of the first teams to arrive on site. During the course of the project, you will find more opportunities to look at any extensions of time required, variations in the contract and associated payment schedules.

Cash flow is the driving force behind any building project, so monitor it closely and have it on your daily to do list.

You will need to regularly need to walk the site with team leaders to agree progress for payment of completed activities. It is important to adopt a flexible approach here, as sometimes too rigid an interpretation of the term ‘completed’ under the terms of the contract could result in serious cash flow issues for the subcontractor.

Some teams will be keen to get stuck into the project as soon as they see an opening in their own schedules and can be very persuasive in getting you to change your programme to suit them. Only allow this after you have given it enough thought and you are sure that it will not have a negative knock on effect on other activities. It might sound great at the time when someone unexpectedly wants to start early, but it might not be so good for the overall plan.