The EPA’s Code of Practice for Domestic Waste Water Treatment Systems (Population Equivalent ≤10) was published in May 2021, replacing the 2009 version. Here’s what you need to know.

If you’re building in the countryside, chances are that you may not be able to connect to the local authority sewer system. This means you will need some way of dealing with the wastewater you generate.

In ROI, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Code of Practice is the statutory reference document that explains how to tell if your site is suitable for an onsite wastewater treatment system, and if so, what options are open to you.

If your site is not suitable for an onsite wastewater treatment system, and there is no mains connection, you could be denied planning permission to build a house on that site. The situation is different in NI (see Basics guide p88).

Although the structure of the Code has changed somewhat since the 2009 version and it does include welcomed clarifications, much of the technical detail has not changed significantly.

Some examples of changes that have occurred, for instance, are that the new Code now requires a 2m metal perimeter fence around soil based constructed wetlands, which will add to costs and present aesthetic challenges.

[adrotate banner="58"]Also, the depth of subsoil required beneath raised mound filter beds has increased to 0.9m which means that on some sites with very clayey soil, a raised bed is no longer an option.

The required frequency for desludging septic tanks has been updated too, according to size of tank and number of house occupants.

However, the biggest changes have to do with the new options now available for lower permeability subsoils.

Is my site suitable for an onsite wastewater treatment system?

The way to decide if your site is suitable for a wastewater treatment system is to see how quickly, or slowly, the soil can allow water to pass, by assessing the characteristics of the soil profile from a trial hole in conjunction with a minimum of three percolation tests carried out in situ.

A percolation test measures the rate at which water infiltrates down into the soil, and thus how suitable the soil will be in the longer term for effluent filtration and disposal.

The percolation test used to be referred to as the T-test in the 2009 Code; it is now renamed the PV test. The new Code also extended the allowable range of low permeability soils from PV = 75 up to PV = 120, which may seem to be a significant expansion, but unfortunately the nature of the PV scale gives a somewhat exaggerated impression for slower permeability soils.

A more engineering based and transferable representation of the permeability of soils is field saturated hydraulic conductivity (Kfs) where PV = 75 to 120 is equivalent to a relatively small range of Kfs = 44 to 28 mm/d.

Few sites are likely to offer soils in this range, with many areas still presenting much slower percolation because of more clayey soils.

For these, willow evapotranspiration systems may offer a solution in limited cases, but in reality, more strategic thinking is needed at a national level on the use of licensed discharges to surface water, as is the case in NI. Decentralised group schemes should also be explored.

Why did the Code of Practice change?

A significant area of Ireland presents problematic conditions for domestic onsite wastewater treatment, in particular areas with inadequate percolation due to low permeability subsoils and/or insufficient attenuation due to high water tables and shallow subsoils.

If there is insufficient permeability in the subsoil to take the effluent load (i.e. wastewater coming from the house), ponding and breakout of untreated or partially treated effluent at the surface may occur with associated serious health risks.

There will also be a risk of effluent discharge/runoff of pollutants to surface waters and to wells which lack proper headworks or sanitary grout seals.

If you’re building in the countryside, chances are that you may not be able to connect to the local authority sewer system…

To address these problematic areas and allow development while protecting water resources from the risk of pollution by existing septic tanks in these areas – the so-called legacy sites which are being assessed under the National Inspection Plan – alternative wastewater treatment and disposal options are needed.

Hence, the EPA funded field-based research to identify alternative disposal options and investigate their suitability for areas of low permeability subsoils. Options considered and assessed in a series of field studies were pressurised distribution systems and sealed basin evapotranspiration systems.

The results obtained from these trials, many of them through the Environmental Engineering group in Trinity College Dublin, were then used to derive design criteria and to determine the operating limits for these systems in an Irish context. These are now included in the new Code of Practice.

Low-pressure pipe systems (designated Option 4 in the new Code) can now be used as a solution for sites with soil percolation values (PV) up to 90, and drip dispersal systems (designated Option 5) can be a solution for sites with PVs up to 120.

Both require upfront secondary treatment systems and may also need a septic tank to provide primary treatment, depending on the nature of the secondary treatment system used.

Low-pressure pipe distribution

Low-pressure pipe (LPP) systems are relatively easy to build and operate, just needing a pump sump with submersible pump. Treated wastewater from a secondary treatment system is pumped into parallel lateral pipes to distribute the effluent evenly over the percolation area.

For the new low permeability soil range of PV 75 to 90 the total trench length required per person is 28m, equivalent to a trench loading rate of

18 l/sqmd. Note, this length does not have to be in a single trench but can be split into more parallel lengths depending on the space available for the percolation area.

A vital component is the pump, and it needs to be specified for the site according to a proper hydraulic analysis of the full pressurised system. This analysis should be carried out, or checked, by a qualified expert.

A properly designed and installed LPP system requires little ongoing maintenance. However, regular monitoring by the homeowner should be carried out. In particular, the pumping chamber should be checked for sludge accumulation periodically. There should also be cleanout vents at the ends of the pipes that can be used to pump out any accumulated solids in the lateral pipes, in the unlikely event that they do become blocked.

Drip distribution systems

Drip dispersal systems for wastewater dispersal are manufactured by a few companies worldwide; the manufacturer’s specification and guidelines must be followed.

This system is more complicated from an installation perspective than the low-pressure pipe systems as they need a bespoke control panel and special headworks with filters and also require more regular maintenance.

As outlined at the start, they must only be used to disperse secondary treated effluent – septic tank effluent will block the drippers, as we found from bitter experience. The plan area of the field required for percolation is 34 sqm per person (76 ≤PV≥ 90) or

54 sqm per person (91 ≤PV≥ 120), the latter range based on a real loading rate of 2.8 l/sqm per day from our research.

Zone flushing of the system should be automated, with the frequency either based on number of doses (typically every 50 to 200 doses) or on a timed basis (two weeks to six months).

Wastewater effluent screens/filters should be checked on a monthly basis and cleaned if required. It is also recommended to carry out periodic field flush valve maintenance by opening the valves and switching on the pump(s). This is likely to form part of a maintenance contract you will put in place with the installer, but you could do it yourself if you know what you are doing.

Willow evapotranspiration systems

Reed beds and constructed wetlands were already well covered in the previous Code. But this new update now includes evapotranspiration (ET) systems based on the results from a series of full scale field trials using willow trees on a total of 14 systems (10 in County Wexford, two in County Leitrim, one in County Limerick and one in County Louth).

We wanted to see if these systems, which can significantly reduce any effluent discharge to the wider environment, could be a solution for sites that failed the new percolation test upper limit.

The results showed that such open systems are unlikely to be able to act as completely zero-discharge systems in the Irish climate if the in situ low-permeability subsoil is used as a backfill.

Research is therefore being planned to investigate whether partially covered systems can operate as fully zero-discharge systems for the future, and therefore provide a solution for sites that fail the percolation test.

The open systems were, however, shown to promote excellent pollutant attenuation and significantly reduce net effluent discharge to the environment, particularly over the summer period, and so have been included as a viable passive treatment system for either existing (legacy) and/or new developments as effectively tertiary treatment.

The trials have determined realistic crop factors for the Irish climate from which the guideline designs have been produced.

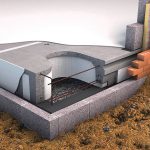

The evapotranspiration systems consist of a basin(s) dug to a depth of 1.8m and lined with an impermeable membrane, to prevent wastewater leaking out and/or groundwater leaking in. Distribution pipes are laid in gravel at the base before the system is backfilled with the in-situ soil that had been excavated, as shown in Figure 3. It is very important that this low permeability soil is broken up by the digger before being replaced in order to achieve a minimum average useable pore space of 15 per cent.

A minimum of three different varieties of willows should then be planted in early spring at a density of three plants per square metre. It is strongly recommended that the ET system is constructed at least one growing season in advance of the inhabitants moving into the house.

These systems are large with a design specification of 187.5sqm per person based on the standard effluent load of 150 litres per person per day. However, it is strongly recommended that water saving technologies are incorporated into a household if using such systems, in which case the sizing can be reduced after consideration by local authorities on a case-by-case basis. For example, if effluent loading is reduced to 100 litres per person per day our research suggests that the evapotranspiration system can be sized at 125sqm per person.

The willow stems should be cut back in the first winter of growth to encourage an increase in stems per plant in the second growing season. Normal coppicing should then take place on a two or three year cycle, with an alternating half or third coppice every year.

It should be noted that these systems, as currently designed, will cause periodic discharges mainly in the winter which either needs to go to a tertiary treatment system or to surface water with an appropriate licence.

However, at present local authorities in ROI do not generally grant surface water discharge consents for single houses.

Cathal Keane of Graf